Rome, September AD 392

[Lucius Apulius narrates. It’s dawn and he’s going to wish his friend and brother in arms, Gaius Mitelus, a good journey as Gaius goes off to join the rival emperor Eugenius’s forces.]

The Mitelus domus wasn’t far away, perched on the summit of the Mons Cispius, part of the Esquiline. The climb up the Cispius was steep and woke me up. That and the stink of donkey dung and the piles of rotting rubbish my servant’s torch lit up. At least at this time of day, or rather night, the smell of hundreds of thousands of people was less oppressive. I did catch the much more welcome smell from a bakery. A group of nightwatchmen were trudging in the opposite direction, probably in search of their beds. One of them glanced up and nodded at me, then went on his way.

When my servant knocked on the service door in the gate of Domus Mitela, the porter took his time answering. I thumped this time and a face with a bad-tempered expression appeared in the cross-barred window within the door.

‘What?’ he grumbled.

‘Open up, for Jupiter’s sake,’ I shouted. ‘It’s Lucius Apulius, senator of Rome, for Gaius Mitelus.’

The window slammed shut and the service door opened instantaneously, held by the porter bowing deeply.

‘I beg you to accept my apologies, your honour. We were not expecting visitors at this hour. It’s as chaotic as Tartarus in here.’

‘Yes, very well. Now is your master up yet?’

‘The Lady Maelia is about and—’

‘Who is the barbarian at our gate?’ Honorina’s voice cut through.

What in Hades was she doing up at this hour at her age, and dressed, as usual, like Juno herself?

‘Apulius! Why are you here? We’re far too busy for visitors,’ she said.

‘I’m fully aware of that, domina. I have come to say farewell to my friend before he enters the snake pit of the court at Lugdunum.’

‘Well described. I tried to dissuade him when he came to see me last night, but he is as stubborn as any Mitelus in history. You’ll find him in the kitchen annoying the staff.’

Thus dismissed, I made my way across the atrium to the back of the house. Gaius was not in the kitchen but the corridor, gulping something down from the cup in his hand in between talking animatedly to one of his Ligurians packing a pair of leather saddlebags. Both turned as my boots resounded on the marble floor. Even in the dim morning light assisted by the flame from the torch in a wall sconce, his face looked like a Greek actor’s with only half the make-up. The lower part was pale, almost white, from being hidden behind the beard now shaved off, the upper part burnt as if made from walnut, and with red-rimmed eyes set in the deep sockets.

‘Lucius! What in Mars’ name are you doing here?’

‘Coming to see you off on your idiot errand.’

‘Don’t you start. I had enough from Aunt Honorina. And Maelia’s been as cold as Tartarus.’

‘Are you absolutely sure you want to go? Eugenius is old school, but Arbogastes would sell his own son, mother and grandmother into slavery to keep in power.’

‘Eugenius isn’t as thick as people think. As master of Valentinian’s correspondence, he was privy to everything and would have worked closely with Arbogastes. And he was declared emperor perfectly normally at Lugdunum.’

‘Normally? What is normal now?’

‘You know what I mean!’

‘Why didn’t you go straight there?’

‘Money, old friend.’ He grinned. ‘I’m going to have to pay my way past all the bureaucrats to reach Eugenius. Honorina blasted me in her usual way then handed over a generous purse of gold. I also needed my formal clothes and my army record.’

He looked so enthusiastic, almost as he was when we were eighteen-year-olds with our first military postings. But as he handed his cup to a waiting slave, I saw his face become serious. At that point, I knew that nothing I could say would dissuade him.

Honorina, leaning on her stick, and I watched as Gaius’s Ligurian adjusted the straps on the pack-mules a groom had brought round to the front. Gaius’s retainers always looked solemn and said little, but this man looked melancholic with deep lines scarring his face.

The street was relatively deserted except for a man with a handcart unloading sacks of grain at the baker’s down the street and two girls hurrying away in opposite directions with loaves under their arms. One shrieked as she almost tripped over a bundle of rags which moved as she approached. A beggar. Perhaps he was waiting for scraps from the baker.

I turned round at the sound of boots clacking on marble. Gaius emerged from the vestibule followed by Maelia at a slow pace. I smiled at her, but she didn’t return it. Gaius pulled me into a bear hug.

‘I bet you wish you were coming with me, Lucius, instead of being stuck with the prosy old senators.’ He grinned at me.

‘No, thank you. I know when I’m well off. And I couldn’t leave the girls. But tell me something… Where’s the other of your Ligurians?’

‘Ah.’ He took a deep breath in. ‘He’s buried in western Gaul.’

‘What happened?’

‘Nothing glorious, although we pretend he fell in defending our employer’s villa against robbers. He went out, got drunk and fell over the wall into the river.’ Gaius pulled a face, then he looked away, the expression on his face markedly darker.

‘I’m sorry to hear that. I know you were close.’

‘That’s how life goes. I try to cheer Ragutius up when he broods, but I think he’s looking for a way out. I keep a careful eye on him. They really were twins and he feels bereft.’

‘Then he’s lucky to have you for a master.’ I paused. ‘Gaius, be careful. Theodosius will see you as supporting a usurper. If Eugenius fails in his bid as Magnus Maximus did, he won’t be as merciful as after Poetovio. Maelia managed to get Marcellus Varus to sell her house so she could pay the fine for Silvanius’s part in Magnus’s bid. This time, Theodosius won’t spare you execution and the Miteli tribe ruin. Think about Honorina at her age, and Maelia and her children.’

‘Then I’d better be successful!’ He clapped me on the shoulder, kissed his aunt and sister on the cheek and then leapt on his horse and rode off into the dawn light. As the noise of the horses’ clip-clop faded, Maelia pulled her palla tighter round her body and said in a voice of utter despair:

‘Will I ever see my brother alive again?’

She turned into her aunt’s arms and wept.

——————

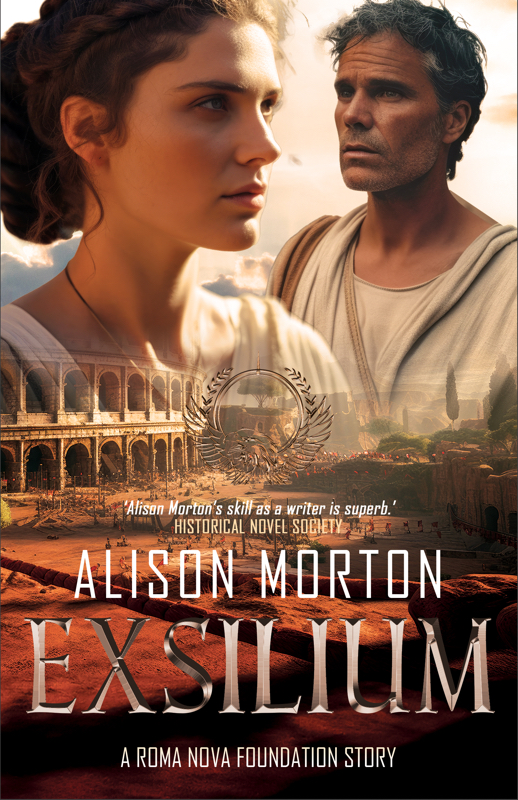

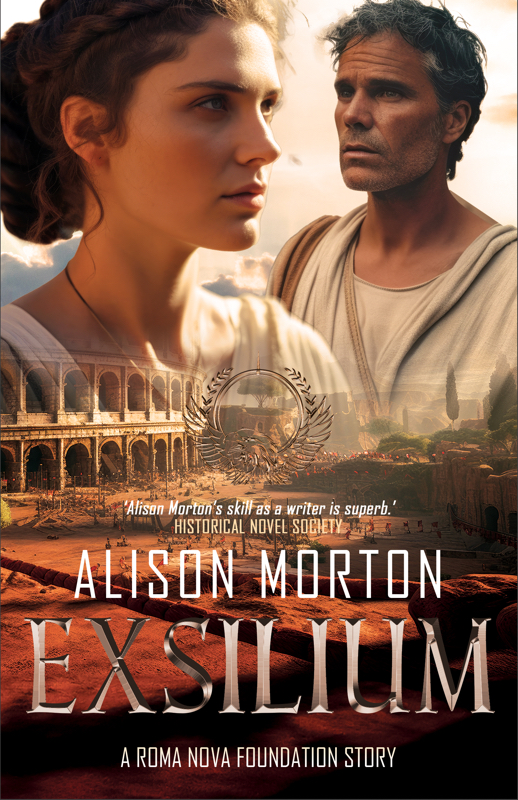

Discover more about Lucius, Maelia (and her brother Gaius) and Lucius’s daughter Galla in EXSILIUM.

Buy the book

Ebook: Amazon Apple Kobo B&N Nook

Paperback: Amazon worldwide Barnes & Noble (more retailers to follow)

——————

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. JULIA PRIMA, Roma Nova story set in the late 4th century, starts the Foundation stories. The sequel, EXSILIUM, is out on 27 February 2024.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

If you enjoyed this post, do share it with your friends!Like this:Like Loading...

Our group of authors contributing to Historical Stories of Exile was delighted to receive this warm review from the Historical Novel Society.

I have to admit that I was particularly chuffed to see a special mention for my story ‘My Sister’ which features Marcellus Virus and his nightmare of a sister, Flavola, two characters who appear in my new book EXSILIUM out later this month.

“My Sister” by Alison Morton is a vivacious tale of sisterly troublemaking and high-stakes politics in ancient Rome. The Roman details and long-suffering narrator make this tale thoroughly enjoyable.”

Ooo!

Here’s an excerpt from My Sister

Rome AD 395. Marcellus Varus (narrating) is attending a dinner party with his sister, Flavola. He’s chatting with friends Lucius Apulius and Gaius Mitelus before eating.

‘How’s your sister taking it?’ Gaius asked me, nodding to the group of women where Flavola stood with a sullen expression.

‘Ah. Well, I…’

‘What?’

‘I haven’t exactly told her yet.’

Lucius looked at me in disbelief. Gaius collapsed laughing. The group of women turned and stared at the outburst of noise. Even the dozen or so other men at the back of the atrium sent puzzled looks at us. After a heartbeat, they returned to their talking. Maelia looked across the room and frowned at us. Lucius took my arm and hustled me into a side room. Gaius followed, still chuckling.

Lucius pushed me down onto a stool.

‘Are you seriously saying that you haven’t told Flavola you’re uprooting her from Rome, from all she knows, and going into voluntary exile?’

‘Look,’ I said, ‘it was hard enough to get her here tonight. She doesn’t get on with Maelia.’

‘You’re wrong, Marcellus,’ Gaius said. ‘She doesn’t get on with anybody.’

‘Don’t poke at my sister, Gaius. You’re not the easiest piece in the pack.’

So that’s all going to go well…

––––––

The full list of contributing authors: : Annie Whitehead, J.G. Harlond, Helen Hollick, Anna Belfrage, Elizabeth Chadwick, Loretta Livingstone, Elizabeth St.John, Charlene Newcomb, Marian L Thorpe, Amy Maroney, Cathie Dunn and Cryssa Bazos. Deborah Swift gave us a brilliant introduction.

You can buy Historical Stories of Exile here: https://mybook.to/StoriesOfExile

––––––

My novel about the Romans and what drove them to their exile, EXSILIUM, is out on 27 February, but you can pre-order the ebook now:

Amazon: https://mybook.to/EXSILIUM

Other retailers: https://books2read.com/EXSILIUM

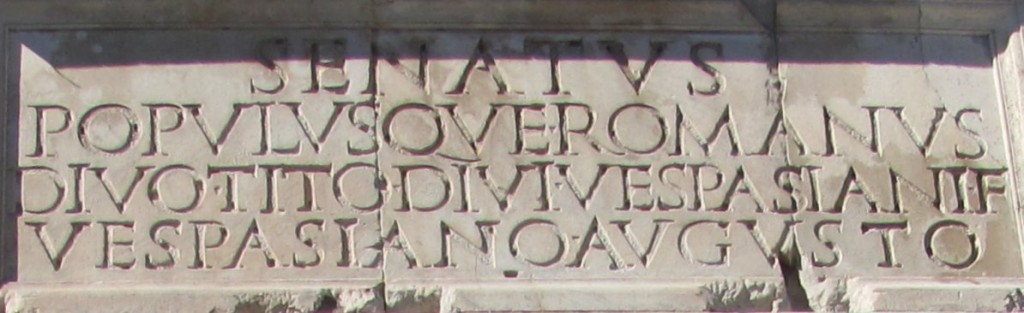

Exile – Living death to a Roman

AD 395. In a Christian Roman Empire, the penalty for holding true to the traditional gods is execution.

Maelia Mitela, her dead husband condemned as a pagan traitor, leaving her on the brink of ruin, grieves for her son lost to the Christians and is fearful of committing to another man.

Lucius Apulius, ex-military tribune, faithful to the old gods and fixed on his memories of his wife Julia’s homeland of Noricum, will risk everything to protect his children’s future.

Galla Apulia, loyal to her father and only too aware of not being the desired son, is desperate to escape Rome after the humiliation of betrayal by her feckless husband

For all of them, the only way to survive is exile.

EXSILIUM is the sequel to JULIA PRIMA and the two books make up the Foundation strand in the Roma Nova series.

Happy reading!

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. JULIA PRIMA, Roma Nova story set in the late 4th century, starts the Foundation stories. The sequel, EXSILIUM, will be out on 27 February 2024.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

If you enjoyed this post, do share it with your friends!Like this:Like Loading...

Photo courtesy of Jessica Bell (http://www.jessicabellauthor.com) Disruptive didn’t begin to describe it. I would have a family there, I’d be comfortable materially, and I would be able to keep my father’s legacy. But every tiny thing would be different.

I’d been forced, sobbing, from my East Coast home after Dad died, and dumped in the Midwest when I was twelve and survived. I’d escaped that bleakness and settled in New York, and adapted. Hell, given the choice between twenty years shut up in a miserable penitentiary and another move, I knew which I needed to pick. I could do this.

Thus Karen/Carina in INCEPTIO, faced with the prospect of having to make a rapid decision about fleeing to Roma Nova.

She’d been through abrupt life changes before; both parents dead, her place in the world uncertain, a contrast in the physical landscape, dutiful but loveless carers and the resulting mental and emotional upheaval. But even as she thinks about the seemingly outlandish option of moving to Roma Nova, she acknowledges her ability to survive and adapt.

Most of us don’t have to make such abrupt decisions, but what should we consider if our careers or life changes mean we leave the culture we know to live in another?

Karen instinctively uses coping techniques innate in human beings since they first lived in communities. We learn from very early childhood how to distinguish ourselves from others and how to interact with to different types of people, starting with our parents and first friends. At school, we learn, sometime brutally in the playground, how to maintain our own identity and fend off those who would exert power over us. Or we adapt and accept a subordinate place. It’s a jungle environment and lessons can be harsh. But school is also where we accumulate knowledge and possibly insight about the world outside our own bubble works. And where we learn how to learn.

So perhaps we are more equipped that we think we are, some people more than others.

Realising what you don’t know

In INCEPTIO, Karen, now reverting to her birth name of Carina, stays in the Roma Nova legation at first and realises what she doesn’t know – she unconsciously triggers her ‘survive and adapt’ strategy by identifying her needs:

I figured out Plica, Editio, Promere for File, Edit, View and Mittere for Send, but had to give up after that. I jabbed at the screen to log out. It was ridiculous; I couldn’t do the simplest thing without the language.

She starts language lessons:

“At the end of the third hour, I had mastered the declensions and simple verbs. I was relieved that I remembered some of it from Latin class as a kid.”

Importantly, she bolsters her confidence by recognising she already has some knowledge to fit her to her new environment.

Building upon the basics

Later in the legation after a few weeks…

I was getting there with my new culture – I guessed it was being surrounded by it all day, every day. […]When Conrad was on duty, and I didn’t have a class, I often retreated to the mess bar and talked to Dexia or some of the others. They were tough-talking but natural. When I tried out my Latin on them, they laughed sometimes, but weren’t too rude about my mistakes. But I couldn’t always follow the flow of the conversation, the inferences or the profanities. I needed to get beyond Grattius’s formal teaching.

So she finds that invaluable resource, a teenager:

‘Very well, Aelia, I’m trying to learn Latin – I was born here in America. I need a friend who’ll teach me everyday Latin words, normal life words. If you want, I can talk to you about America, teach you some English.’

At first, she hesitated. Maybe she thought I was joking, or mocking her. She had to know exactly who I was.

‘Of course, you have to teach me the b ad words as well.’

She grinned. ‘Oh, I know a lot of those.’

Why is social integration important?

You simply can’t live in another country and not be social. You are the outsider, you need to fit in, not only to make practical life easier, but for your own mental and emotional well-being. Studying and working provide valuable opportunities for integration; often the most important lessons learned are outside the formal framework, for instance, from the opportunities for socializing. Ditto if you have an interest or hobby that crosses frontiers.

‘Marrying into’ the new culture means you have to deal with everyday matters, the nitty-gritty of life like running a house, dealing with the local council, the neighbours, the school if you have children, doctors’ surgery, registering a new car or a small business, banking, food shopping, holidays, etc. etc.

Sometimes, even after years, something reminds you of being an outsider. When Karen now Carina, the successful career woman and imperial councillor, flounders about a formal process in SUCCESSIO, her daughter Allegra knows the routine better than her mother does – she’s a born and bred Roma Novan, unlike Carina.

Language and culture are two main factors. In a country where you speak a different language, integration can be hard without at least some basics. Where values are dissimilar, it can take an enormous effort over years to fully understand the psyche of a new country, society and culture.

So how to succeed in settling into a new culture?

Initial stage

- Learn the language – do this before you move and make it a priority when you arrive.

- Eat locally – much better to learn how eat local food in a restaurant than in more personal surroundings when invited for dinner at somebody’s home.

- Become involved in the community – join a history, computer, sport, gardening or book club; if religious, a congregation

- Show interest in other people’s lives, work and hobbies at every opportunitiy

- Offer to help with things you know

- Ask for help for yourself – people are usually generous if you are genuinely struggling

Middle stage

- Accept that the new life is going to be different in both big and small ways.

- Understand that shifting your norms of behaviour, of instinct, takes time and practice.

- Observe closely subtle understandings and interactions learnt from childhood between native-born people.

- Accept you are going to feel awkward, possibly uncomfortable and make mistakes. Make sure you forgive yourself when this happens – it’s perfectly normal.

- Finding a ‘cultural mentor’ who knows both your and the new culture’s ways will ease the way considerably.

In INCEPTIO, Aurelia, being a clever woman, has worked this out and assigns a younger member of the Mitela clan, Helena, to take Carina under her wing. Not that Helena is very happy about this, but she does her duty…

- Talk to somebody about the disparity and how uncomfortable you feel about certain aspects of your cultural crossing. If you are staying, as Carina is, you have to accept you will have to break out of your comfort zone to some degree.

- But, make sure you still retain who you are, your inner core, your personal values.

Final stage

One day you wake up and find you are actually more at ease in your adopted country that you were in your original one. You made it!

Troops marching hard – column of Marcus Aurelius (Creative Commons licence) The ultimate secret to success?

The key is making an effort.

Show others you’re enthusiastic about learning their cultural rules, even though you might not have mastered them, and that you care about and respect their traditions. Yes, it is hard work at first, but if you persist you will build cultural capital that will make your life richer and more comfortable, and, if you move again, capital you can cash in in any foreign setting.

Updated February 2024: Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. JULIA PRIMA, Roma Nova story set in the late 4th century, starts the Foundation stories. The sequel, EXSILIUM, will be out on 27 February 2024.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

If you enjoyed this post, do share it with your friends!Like this:Like Loading...

|

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Join 37 other subscribers.

Buy AURELIA from Apple!

UK

US

|