Welcome to the home of the Roma Nova thrillers. Please look around while you are here.

When two people meet formally for the first time, it’s customary to shake hands. Similarly, it’s something you do on parting, offering congratulations, expressing gratitude, or completing an agreement. In sports or other competitive activities, it’s also done as a sign of good sportsmanship. Its purpose is to convey trust, balance, and equality.

When two people meet formally for the first time, it’s customary to shake hands. Similarly, it’s something you do on parting, offering congratulations, expressing gratitude, or completing an agreement. In sports or other competitive activities, it’s also done as a sign of good sportsmanship. Its purpose is to convey trust, balance, and equality.

Research at the Weizmann Institute shows that human handshakes serve as a mean of transferring social chemical signals between the shakers. Apparently, we tend to bring the shaken hands to somewhere near our noses and perform an olfactory sampling of it. This may serve an evolutionary need to learn about the person whose hand was shaken, replacing a more overt and less socially acceptable sniffing behaviour, as common in other animals like cats and especially dogs.

How long have we done it?

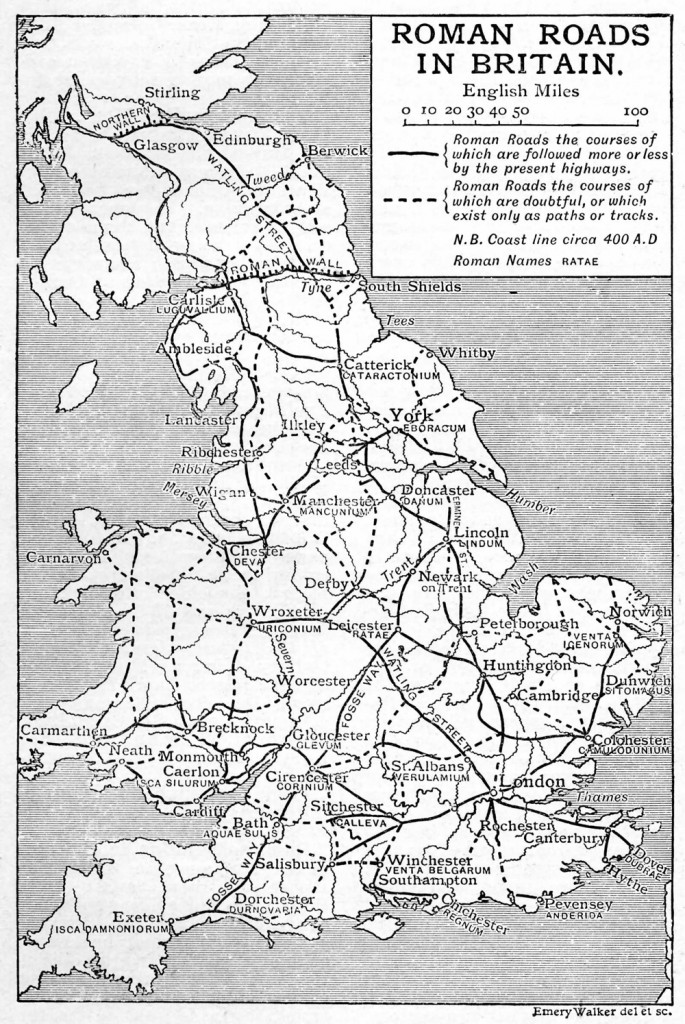

Archaeological ruins and ancient texts show that handshaking was practiced in ancient Greece as far back as the 5th century BC. This is more of a full clasp, not just fingers – note the position of Athena’s thumbs on Hera’s wrist.

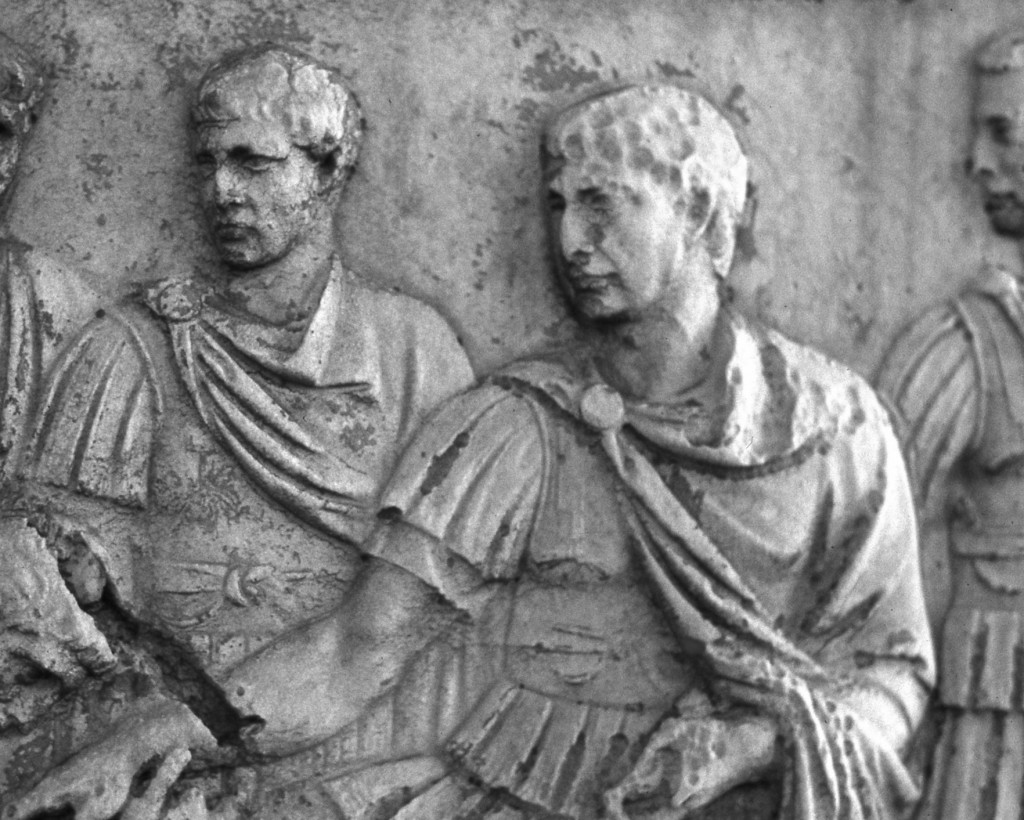

The handshakes on funerary reliefs or coins in Roman imperial times, the dextrarum iunctio (joining of right hands), were mainly ceremonial, although expressing a strong bond, e.g. between man and woman on marriage (right), sometimes between patrons and freedmen, sometimes of an agreement between two communities or of a sign of peace.

The joined right hands were also used as a sign of friendship, hospitality and community. Perhaps the gesture was used when people greeted each other in formal situations rather than as an everyday gesture.

The ‘Roman’ forearm handshake

To my great disappointment, the forearm handshake is considered today to be pure Hollywood.

Instead of exchanging handgrips, the two clasp each others’ forearms, just below the elbow. It seems more martial and physical, something fitting with the audience’s expectations of a very physical and martial society like Rome. It’s a rather romantic, possibly nostalgic, manly idea of camaraderie.

However, there seem to be no Roman era depictions of this handshake. As we saw above, there is plenty of evidence of ordinary handshakes from the Roman era, so we have to conclude that it’s a later invention. It may originate from the theatre where actors wanted to make the handshake look dramatic and to emphasise comradeship and male bonding.

One interesting speculation is that the forearm handshake was taught to the actors by painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema in a 1898 staging of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. During this time, Alma-Tadema was very active with theatre design and production. His meticulous archaeological research, including research into Roman architecture (which was so thorough that every building featured in his canvases could have been built using Roman tools and methods) led to his paintings being used as source material by Hollywood directors in their vision of the ancient world for films such as D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), Ben Hur (1926) and Cleopatra (1934). The designers of the Oscar-winning Roman epic Gladiator used the paintings of Alma-Tadema as a central source of inspiration.

Shaking hands could be seen as a relic of our ancient past. Whenever primitive tribes met under friendly conditions, they would hold their arms out with their palms exposed to show that no weapons were being held or concealed. Could it be that in Roman times the practice of carrying a concealed dagger in the sleeve was common so for protection the Romans developed forearm handshake as a common greeting?

We’ll never know.

But in a speculative departure from concrete knowledge, I’ve slipped it in here and there in my Roma Nova novels and female soldiers like Carina and Aurelia use this form when greeting their military colleagues.

Sorry, purists!

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. JULIA PRIMA, Roma Nova story set in the late 4th century, starts the Foundation stories. The sequel, EXSILIUM, is now out.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.