I expect we can all name a number of famous exiles without too much bother – Napoleon Bonaparte, Leon Trotsky, Benazir Bhutto, Roman poet Ovid, Marlene Dietrich, Aristotle, the von Trapp family, Albert Einstein, to name but a few.

Exile is essentially a separation from your homeland and can be temporary or permanent. Sometimes it can be enforced such as by deportation, or voluntary, when you become fed up with that homeland or you see the writing on the wall and leave before you are prosecuted, persecuted or worse. Sometimes, a country is relieved when a tyrant is deposed and sent into permanent exile, or saddened when it’s invaded by the bad guys and they must ensure said bad guys do not capture symbolic people such as the Norwegian and Dutch monarchs in the Second World War.

‘Diaspora’ describes group exile, both voluntary and forced. ‘Government in exile’ signifies a government of a country that has relocated to a safer one and argues its legitimacy from outside that country.

Romans and exile – a complicated business

Ancient Roman law actually adopted the penalty of exile in an effort to avoid excessive capital punishment. (Interesting, in light of the studied brutality of the many games in the amphitheatre…) In addition, while the death penalty offered no flexbility, the idea of different degrees of exile allowed the state, or ruler, to impose a punishment that matched the severity of a particular crime.

Polybius, the Roman historian, says, “Men who are on trial for their lives at Rome, while sentence is in process of being voted – if even only one of the tribes whose votes are needed to ratify the sentence has not voted – have the privilege at Rome of openly departing and condemning themselves to a voluntary exile. Such men are safe at Naples or Praeneste or at Tibur, and at other towns with which this arrangement has been duly ratified on oath.” (Histories 6.14)

According to Cicero, exsilium was a voluntary act through which a citizen could avoid legal penalty by leaving the community, i.e. choosing to avoid imprisonment, death, or dishonour. In essence, that citizen could take refuge in exile and still retain their legal citizenship. (Cicero, In Defence of Caecina)

But it’s not that straightforward

We often use banishment and exile interchangeably, but the two words do have distinctive meanings, the first is imposed, the second voluntary. Flight, or fuga, was considered the more voluntary option of exile, whatever the motivation, pressures or threats triggering it. In contrast, banishment is exile by forced removal.

Furthermore, banishment can be broken down into three levels of severity; relegatio, aquae et ignis interdictio, and deportatio. The severity of the punishment is measured by the duration, location, and rights associated with each of the three tiers.

Relegatio

The mildest form of banishment is called the relegatio. The relegatio is removal of citizens or foreigners from Rome or a Roman province by magisterial decree for a specified amount of time or for life. A person subject to relegatio is ordered to leave Rome by a certain date; however they are not sent to a designated location or do not lose any of their civil rights.

Aquae et Ignis Interdictio

Literally meaning ‘debarred from fire and water”, i.e. they are deprived of the chief necessaries of life. This was mainly used as a sanction during the Republican period. This second tier was similar to the first in the sense that the exiled person had no permanent place of residency. However, aquae et ignis interdictio differed in terms of duration and rights. The victim lost the civil rights that came with Roman citizenship and their property was confiscated. Aquae et ignis interdictio was occasionally was applied to unique cases of voluntary exile, or self-banishment. Despite voluntary departure, the person was still stripped of rights and property.

Literally meaning ‘debarred from fire and water”, i.e. they are deprived of the chief necessaries of life. This was mainly used as a sanction during the Republican period. This second tier was similar to the first in the sense that the exiled person had no permanent place of residency. However, aquae et ignis interdictio differed in terms of duration and rights. The victim lost the civil rights that came with Roman citizenship and their property was confiscated. Aquae et ignis interdictio was occasionally was applied to unique cases of voluntary exile, or self-banishment. Despite voluntary departure, the person was still stripped of rights and property.

Deportatio

Deportatio was the hardest level of banishment. It required forcible removal to a fixed place, most commonly an island in the Mediterranean, usually until death, whether that came sooner or later. Many deportees were dumped on an island with few resources of food and water and so starved to death. The English word ‘deportation’ means to expel a foreigner from a country, typically on the grounds of illegal status or for having committed a crime.

Location, location, location

The place of exile was usually related to the prescribed duration, whether it was temporary or for life. If only banished for a fixed period of time, the extent of the exile’s desire to remain involved in political or social life became of great importance in relation to where he spent his time away from Rome. These factors contributed heavily to determining the destination for exile. It could be only as far as Naples. Sometimes, the exiled person could choose, as long as he or she remained a given number of miles away from Rome.

In AD 8, Ovid was banished to Tomis, on the Black Sea, by the exclusive intervention of the Emperor Augustus without any participation of the Senate or of any Roman judge. Ovid wrote that the reason for his exile was carmen et error – a poem and a mistake, claiming that his crime was worse than murder, more harmful than poetry. To this day, scholars and everybody interested in Roman history are dying to know exactly what Ovid had done!

Is exile all bad?

Separation from Rome, its politics, the family and above all the intrigue and gossip, could be a very harsh punishment, but there were some plus sides (not if you were starving on a rock in the middle of the sea, though). It was a kinder penalty than execution. It could offer hope of a return. And in some cases, it led to unexpected outcomes.

Rome itself is said to owe its rise to exiles. Aeneas, a major figure in the Roman foundation myth, was driven from his Trojan home and led his followers to Italy where his descendants would one day found Rome. Moreover, Romulus populated his newly established city with riff-raff of every kind – prisoners of war, slaves, criminals and exiles. And Ovid? Some of his greatest work including the Tristia and the Epistulae ex Ponto owe their creation to the poet’s banishment.

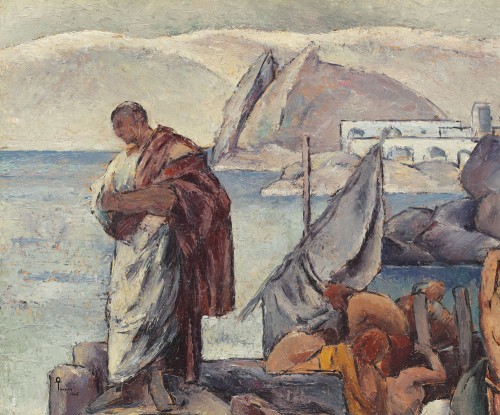

The characters in EXSILIUM are more Cicero’s type of voluntary exiles. The three desires of fleeing persecution, a wish to guarantee safety for their children and the freedom to practise their traditional religion were very strong motivations!

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. JULIA PRIMA, Roma Nova story set in the late 4th century, starts the Foundation stories. The sequel, EXSILIUM, will be out on 27 February 2024.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Really interesting,Alison. I’m wondering now what Ovid had done!

Well, there have been rumours flying around throughout the centuries! Did he sleep with a relation of the emperor and get caught? Did he see or hear something he shouldn’t have? Did he say something to somebody close to the emperor who was offended and insisted the emperor exile the poet? It’s one of those mysteries that only a time machine could solve. 😉