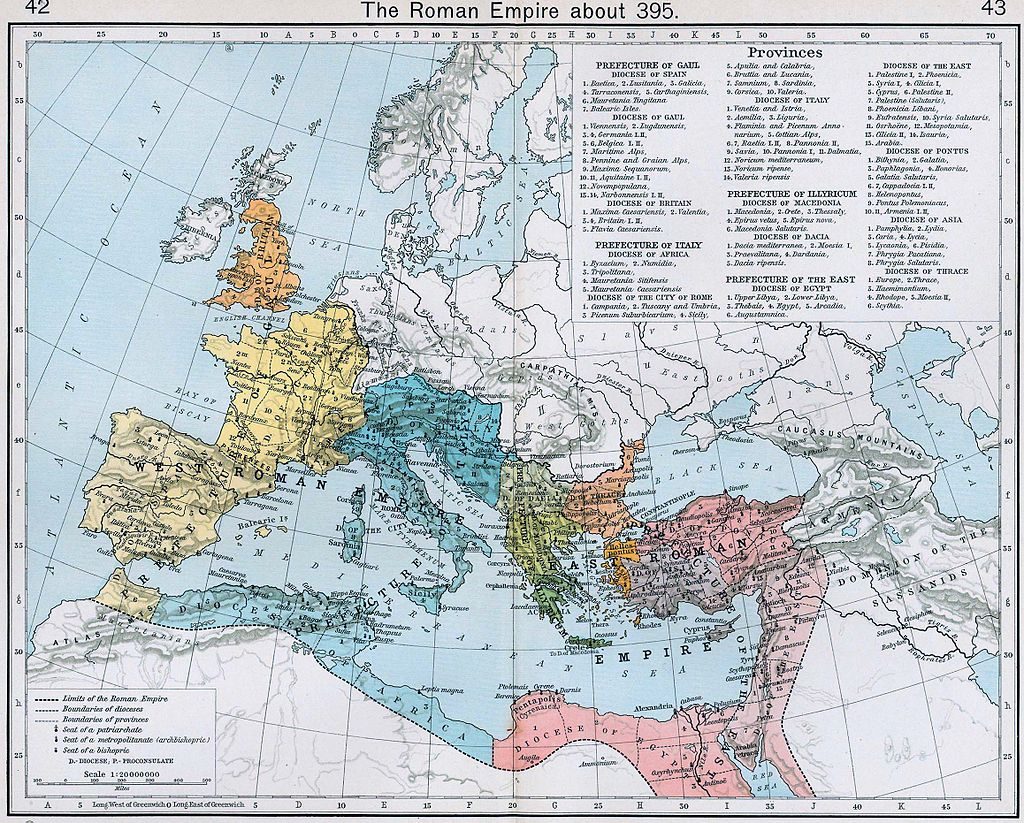

In the Roma Nova story, over four hundred Romans loyal to the old gods trekked north out of Italy in AD 395 to a semi-mountainous area similar to modern Slovenia.

Led by Apulius and his friend Mitelus at the head of twelve senatorial families, they established a colony based initially on land owned by Apulius’s Celtic father-in-law.

By purchase, alliance and conquest, this grew into Roma Nova, as portrayed in the modern era in the Roma Nova thrillers.

But what was that crumbling Roman world of AD 395 like that prompted the two friends to escape?

Rome – a tale of two cities

The Roman empire had changed in many ways since the time of Augustus nearly four hundred years before; the East, centred on the well fortified and connected Constantinople, continued to grow in importance as a centre of trade and imperial power while Rome itself diminished greatly in political importance.

Ambrose barring Theodosius from Milan Cathedral, Anthony van Dyck, c. 1620 (Reckoned now to have been a greatly exaggerated event!)

Christianity was enforced as the official state religion; Theodosius had issued edicts during the 390s banning pagan religious practice, closing temples and dousing the sacred flame that had burnt for over a thousand years. Although the senatorial classes that Apulius and Mitelus belonged to held on to their traditions, across the empire the old pagan culture was disappearing.

The West outside Rome and other large cities, less urbanized with a spread-out populace, experienced economic decline throughout the Late Empire, especially in outlying provinces such as southern Italy, northern Gaul, Britain, to some extent Spain and the Danubian areas.

After emperor Gallienus banned senators from army commands in the mid-3rd century, the wealthy senatorial elite lost experience of, and interest in, military life. Sons did join the army – some senatorial families believed military experience in early adulthood made tougher men later – but they left early as the career path was blocked.

Unfortunately, as it headed towards the 5th century, the remaining landowning elite of the Roman senate not only largely barred its tenants from military service but also refused to approve sufficient funding for maintaining a sufficiently powerful mercenary army to defend the Western Empire. Not the best strategy ever. By AD 394, 200,000 soldiers guarded the borders with a reserve force of 50,000. Many of the non-Roman soldiers who made up these forces came from Germanic tribes: Alamanni, Franks, Goths, Saxons and Vandals.

After AD 394, the new Western government installed by Theodosius I increasingly had to divert military resources from Britain and the Rhine to protect Italy. This, in turn, led to further rebellions and civil wars because the Western imperial government was not providing the military protection the northern provinces expected and needed against the barbarians.

As central power weakened, the state gradually lost control of its borders and farther-flung provinces, and with the Vandals conquering North Africa, it lost control over the Mediterranean Sea, the hallowed Mare Nostrum (‘Our Sea’). Basically, the imperial authorities had to cover too much ground with too few resources. In many places, Roman institutions collapsed along with economic stability. In some regions, such as Gaul and Italy, the settlement of ‘barbarians’ on former Roman lands seemed to be accepted and caused relatively little disruption.

Theodosius died in AD 395 at 48 years old and with him went the strong government imposed by his will. The empire split again into two, his sons Honorius took the West, and Arcadius the East.

The Roman Empire lost the strengths that had allowed it to exercise effective control: the declining effectiveness and numbers of the army, lower agricultural yields, thus poorer health and numbers of the Roman population, less tax revenue from fewer productive lands, less frequent use of trading routes due to lower production of goods.

Long-distance markets disappeared thus undermining the stability of the economy and its complexity, technological and engineering knowledge faded within a few generations, the whole compounded by the decreasing competence of the emperor, the religious upheavals, and diminishing efficiency of the civil administration, not to mention increasing pressure from ‘barbarians’ outside Roman culture.

As the once powerful empire fragmented, people reverted to more of a subsistence economy, to a greater degree of local production and consumption, rather than webs of commerce and specialised production Its society was unravelling, collapsing from inside. By AD 395 the Roman Empire was firmly on its way to becoming a failed state.

And for traditional Romans like Apulius, Mitelus and friends?

The Late Antique period saw a wholesale transformation of the political and social basis of life. The Roman citizen elite in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, under the pressure of taxation and the ruinous cost of presenting spectacular public entertainments in the traditional cursus honorum, had found under the Antonines that security could only be obtained by combining their established roles in the local town with new ones as servants and representatives of a distant Emperor and his travelling court.

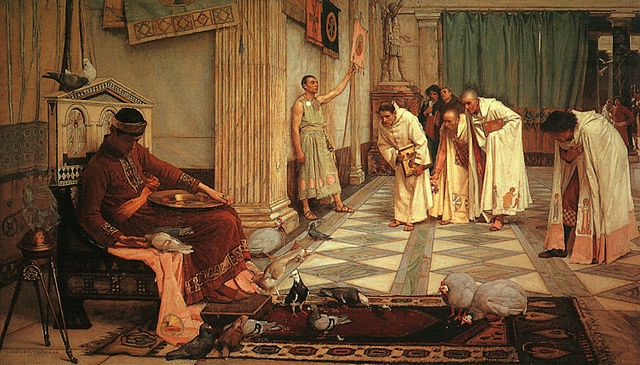

After Constantine centralised the government in his new capital of Constantinople in AD 330, the Late Antique upper classes were divided among those who had access to that far-away centralised administration and those who did not. Although well-born and classically educated, election by the Senate to magistracies was no longer the path to success. Room at the top of Late Antique society involved increasingly intricate channels of access to the emperor.

The plain toga that had identified all members of the Republican senatorial class had given way to the silk court vestments and jewellery that we associate with Byzantine imperial iconography. The imperial cabinet of advisors, the consistorium, was made up of those who were prepared to stand in courtly attendance upon their seated emperor, as distinct from the informal set of friends and advisors surrounding Augustus. Thus, Romans in the city of Rome like Apulius and Mitelus were stranded from power, yet caught by their inbred loyalty to the emperor.

In mainland Greece, the inhabitants of Sparta, Argos and Corinth abandoned their cities for fortified sites in nearby high places. In Italy, populations that had clustered within reach of Roman roads began to withdraw from them, as potential avenues of intrusion, and to rebuild in typically constricted fashion round an isolated fortified promontory, or rocca. In the Balkans, inhabited centres contracted and regrouped around a defensible acropolis, or were abandoned.

Thus, four hundred Romans trekking out of their once glorious, teeming and powerful city to a mountainous region in the north in order to preserve their way of life religion and culture was far from unusual. You can read why and how they went into voluntary exile in EXSILIUM.

The next trick was to survive.

————–

Book recommendation: The Fall of the Roman Empire and the End of Civilisation, Bryan Ward-Perkins, (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Updated 2023 and 2024: Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. JULIA PRIMA, Roma Nova story set in the late 4th century, starts the Foundation stories. The sequel, EXSILIUM, is now out.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Strong history lesson for so early in the morning, Alison! But all fascinating stuff. Look forward to that novel you’re poised to write when you go back all that way in time to see how Roma Nova started!

Thanks, Fenella. That novel is still in the mists of the future, but I’m planning…

Not too far into those future mists, one hopes…

The idea of the foundation story is swirling around in my head, gestating nicely! But before that the sixth book, RETALIO, will be hitting the shelves in spring….

That was an excellent history lesson since most historical fiction doesn’t focus on the fall of the Roman empire. And I am definitely excited that you’re planning to write about the founding of Roma Nova after you finish Aurelia’s story.

Thank you, Juliet. I’m really pleased you enjoyed it. The ‘fall’ was quite a long process of dissolution and fragmentation and is incredibly complex. A fascinating period when you start looking at it…

The third part of Aurelia’s story, RETALIO, will be out in spring. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed writing it and I think it’s given readers of the first trilogy some background of Carina’s story as well.

You make me want to go back to Rome and get my old Latin books out again.

Sadly, Rome AD 395 was not as glorious, prosperous or stable as in the ‘golden’ years of the empire, but like all changing periods, it was certainly interesting!

Wow, fascinating Alison! I hadn’t realised all the implications of what I knew of this period. Well done.

Times of change are the most interesting as well as the most elusive!

[…] http://www.alison-morton.com/2016/11/21/the-roman-world-in-ad-395/ […]