Travelling in the ancient world was different, fundamentally different. Young (and not so young) men were by far the most mobile in the Ancient Rome over the whole period whether you count it to AD 476 (west) or 1453 (east) because they fought in armies. Next came the administrators, posted in a similar way to the military, to freeze their extremities off in Germania or Britannia for boil their brains in the provinces of Syria or Egypt. Both would be served by official couriers, messengers and supply chains speeding along the famous Roman roads serviced by way stations with basic personal resupply and accommodation facilities (mansiones).

Merchants, of course, were very familiar with trade routes; the same ones were used for hundreds of years. Wealthier individuals made journeys for education and recreation and their households (free or slave) went with them.

Roman travelling coach carpentum (reconstruction), in the Römsich-Germanischen Museum in Cologne, Germany

Travel could be on horseback, ox cart, litters, travelling coaches, ship, barge, mules or Shanks’s pony (on foot). Soldiers just yomped with baggage trains trailing behind them, although to keep these baggage trains from becoming too large, in 107 BC General Gaius Marius made each man carry his own armour, weapons, personal equipment and 15 days’ rations, about 50–60 pounds (22.5–27 kg) in total.

Legionaries were issued with a forked stick to carry their load on their shoulders and were nicknamed Marius’ Mules (muli mariani in Latin) due to the amount of gear they had to carry themselves.

Officers like my tribune Lucius Apulius in JULIA PRIMA would have ridden a horse, had a servant riding a mule and made use of the mansiones if travelling away from his unit or between postings. At a fort, they would be lodged with other officers and even dine with the commander. Which is what happens to Apulius on his long journey from Britannia to Virunum in Roman Noricum (approximately modern Austria). But he was rained on and hated sleet and snow like any other serving soldier and was pleased to be wearing his paenula scortea, leather poncho as he rode along.

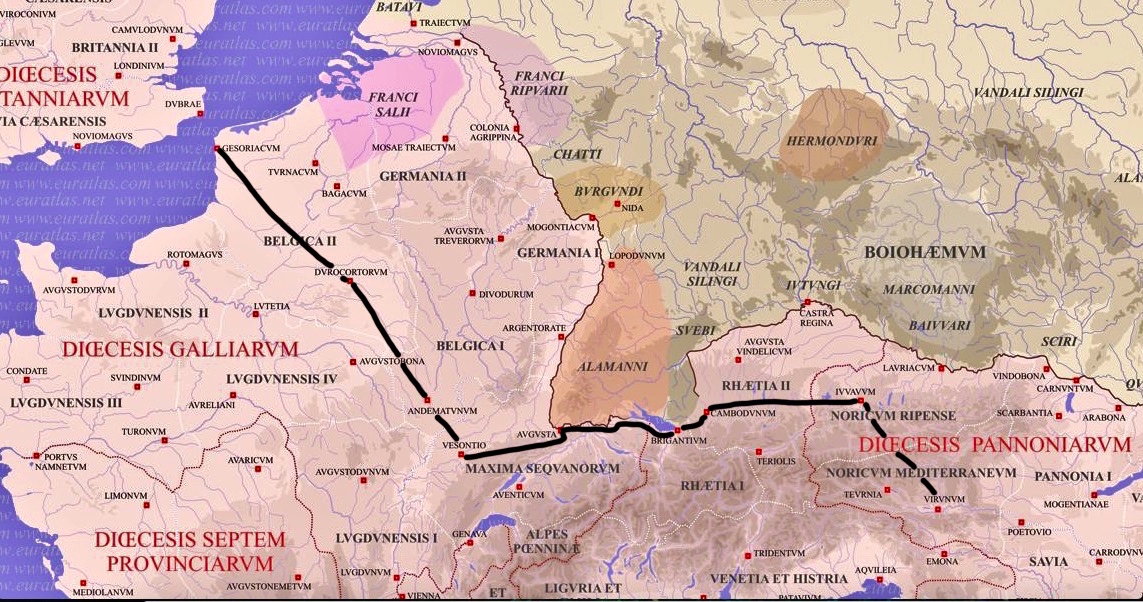

So what route did Apulius take in AD 370?

Firstly, he took a ship (military transport) across the Oeanus Britannicus from Dubris to Bononia (called Gesoriacum until the end of the third century), then on to Durocortorum (Rheims) and Vesontio (Besançon) on horseback. Apart from his own horse and the mule his servant rode, Apulius hired a travelling cart with driver and relief driver for his belongings and equipment.

Then it started to get sticky…

The Roman Empire’s effective northern border (limes) in AD 370 ran along the line of the the Rhine and Danube rivers. Today, the passage along the upper Rhine valley via Basel is an important transalpine route with a multi-lane motorway and railway line; in Apulius’s time it was a vital axis between Gaul and the East. If control of that passage was lost, the empire would be split in two.

The city of Augusta Raurica to the east of today’s Basel was a prosperous trading town whose innkeepers and traders probably made a tidy profit from passing trade. However, about AD 300, following the loss of the right bank of the Rhine, the Roman army built a fort nearby called Castrum Rauracense. During the 4th century, it grew in strategic importance; emperors Constantius II and Julian assembled their armies at the Castrum Rauracense before marching to battle against the Alemanni, the ‘barbarians’ to the north. Given its physical vulnerability after its sacking by the Alemanni in 260 AD, Augusta Raurica was resettled on a much smaller scale on the site of the castrum (modern Kaiseraugst).

Here, Apulius was forced to change to mule trains and military escort. By 370 AD, slow moving carts and sole travellers (servants not counted) would have been easy pickings for any raiding parties. But the route was still relatively safe to Brigantium (Bregenz) where a Roman fleet was based to patrol Lake Constance. Not the easiest command with the ferocious Alemanni across the water, just waiting…

For the next stage, he needed a larger escort as he was crossing an open frontier zone where the risk of conflict with Alemanni war parties was almost inevitable, but once in Cambodumum (Kempten), he was back in Roman territory and relative safety on his way to Iuvavum (Salzburg) and Virunum, his posting in Noricum.

Conveying belongings is easy for us today; we chuck them in the car, or a strong suitcase, a high tech backpack with Wi-Fi connectivity and take a plane or train. Luggage in Apulius’s time was roped packs, panniers on mules, wooden chests on carriages or wagons, none of which was guaranteed waterproof unless covered by leather. (My sincere thanks to fellow scribe Ruth Downie for sending me copies from Lionel Casson’s ‘Travel in the Ancient World’ and Ann Hyland’s ‘Equus: the Horse in the Roman World’ to clarify this.)

And time, it took time. Using Stanford University’s ORBIS and the Italian https://omnesviae.org, I calculated the journey time by each form of transport, double checking distances and physical landscape. And the more obvious routes in the area were starting to be inaccessible, not only from the weather, but as the empire literally lost ground. Apulius took about six weeks altogether.

Virunum amphitheatre during excavation (Photo: Wikipedia). Current photos (and video): https://www.alison-morton.com/2023/06/17/feeling-the-virunum-amphitheatre/

Today, to get to Maria Saal (nearest place to the site of Virunum), you can hop on a plane to Vienna, then one to Klagenfurt, hire a car and be there the same day seeing the same mountains Apulius would have seen. He may even have watched games in the amphitheatre being excavated in the photo above.

Find out what happened when Lucius met Julia, the daughter of Prince Bacausus in Virunum.

Hint – it didn’t go smoothly…

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. JULIA PRIMA, a new Roma Nova story set in the late 4th century, is now out.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Fascinating information. Thank you!

My pleasure, Pamela. A very interesting one to research and one involving a whole mind-shift from the 21st century.

Really interesting. It’s mind boggling to think of lugging all that stuff on long marches – gosh, those Ancient Romans were tough!

Weren’t they just! Mind you, a modern infantry soldier carries a fairly hefty load. In Aghanistan, a load over 100lbs was not uncommon.