No, not the reverse of the Ben Stiller movie, but a completely self-indulgent day at the Museum of London which is where I took these photos.

No, not the reverse of the Ben Stiller movie, but a completely self-indulgent day at the Museum of London which is where I took these photos.

Whenever I view Roman rooms/galleries anywhere, I’m always struck by just how much ‘stuff‘ the Romans left behind. Moreover, what we’ve unearthed was what people threw away, dropped, left by accident or in a panic, or buried. When you think how much more they made, used or treasured in their daily lives, it could blow your mind. And this was in a pre-industrialised society.

I always wonder at the detail of metalwork, the expertise of pottery decoration, the range, number and variety of pots, glass, arms, taps, mosaics and tools we’ve found so far, and that goods came from and went to every part of the Roman Empire and beyond via complex trade routes.

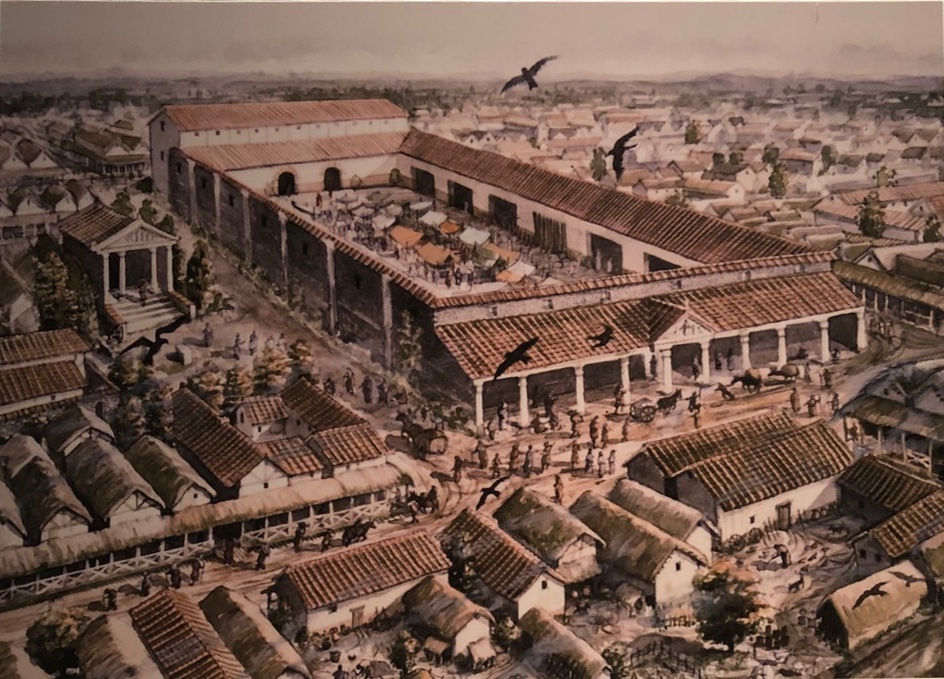

Londinium was reasonably civilised, however it was more than anything a trading port and an admin centre/military station.

Established first in AD 43, it was strategically placed as a transport hub, the centre of a network of roads leading to every part of the new province.

All the Roman civil trappings were there – forum, arena, planned city streets, drains, baths, markets, governor’s palace, basilica, temples, burial grounds, shops – as well as the military forts, barracks and defences.

But it wasn’t always a peaceful development… In 60 or 61 AD, the Iceni rebellion led by Boudica forced the garrison to abandon the settlement, which was then razed. Following the defeat of Boudica by Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, the city was rebuilt as a planned Roman town; first infrastructure and, more slowly, residential buildings.

Two reconstructed rooms, with reconstructed furniture at the museum. Objects are from excavations of Roman London

During the later part of the 1st century, Londinium expanded rapidly, becoming Britannia’s largest city. By the turn of the century, Londinium had grown to perhaps as many as 60,000 people, almost certainly replacing Camulodunum (Colchester) as the provincial capital; by the mid-2nd century, Londinium was at its height. Its forum and basilica were among the largest structures north of the Alps when Emperor Hadrian visited Londinium in 122 AD. Excavations have discovered evidence of a major fire that destroyed most of the city shortly after, but the city was again rebuilt. By the second half of the 2nd century, Londinium appears to have shrunk in both size and population.

Although the town remained important for the rest of the Roman period, there was little further expansion. Londinium supported a smaller but stable settlement population as archaeologists have found that much of the city after this date was covered in dark earth—the by-product of urban household waste, manure, ceramic tile, and non-farm debris of settlement occupation, which accumulated relatively undisturbed for centuries.

In 1999, a highly decorated lead coffin was discovered in Spitalfields containing the remains of a wealthy young woman, her clothes and grave goods from the fourth century AD. Recent research has shown that contrary first thoughts, she originated from Rome itself. The mystery of who she was and why she was there in that unstable period remains unsolved… More here

Sometime between 190 and 225 AD, the Romans built a defensive wall around the landward side of the city. Along with Hadrian’s Wall and the road network, this wall was one of the largest construction projects carried out in Roman Britain. The London Wall survived for another 1,600 years and broadly defined the perimeter of the old City of London.

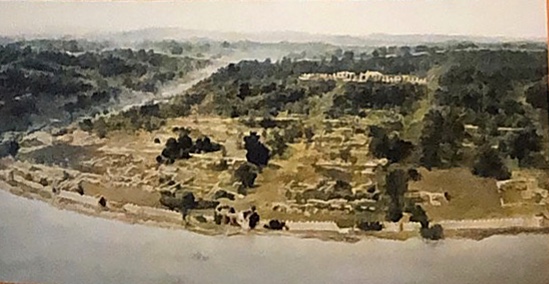

London’s fortunes waned as Britannia was subdivided administratively; Eboracum (York ) became more prominent than before. By the late fourth/early fifth century, the Roman Empire was disintegrating. With few troops left in Britain, many Romano-British towns—including Londinium—declined drastically over the next decades. Many of London’s public buildings had fallen into disrepair by this point. Excavations of the port show signs of rapid disuse.

Between 407 and 409 AD, large numbers of barbarians overran Gaul, seriously weakening communication between Rome and Britain. Trade broke down, officials went unpaid and Romano-British troops elected their own leaders. Constantine III declared himself emperor over the west and crossed the Channel to Gaul, an act considered the Roman withdrawal from Britain since the emperor Honorius subsequently directed the Britons to look to their own defence rather than send another garrison force.

Archaeologists have found evidence that a small number of wealthy families continued to maintain a Roman lifestyle until the middle of the 5th century, inhabiting villas in the southeastern corner of the city and importing luxuries. Medieval accounts state that the invasions that established Anglo-Saxon England (the Adventus Saxonum) did not begin in earnest until some time in the 440s and 450s. Bede recorded that the Britons fled to Londinium in terror after their defeat at the Battle of Crecganford (probably Crayford), but nothing further is said. By the end of the 5th century, the city was largely an uninhabited ruin.

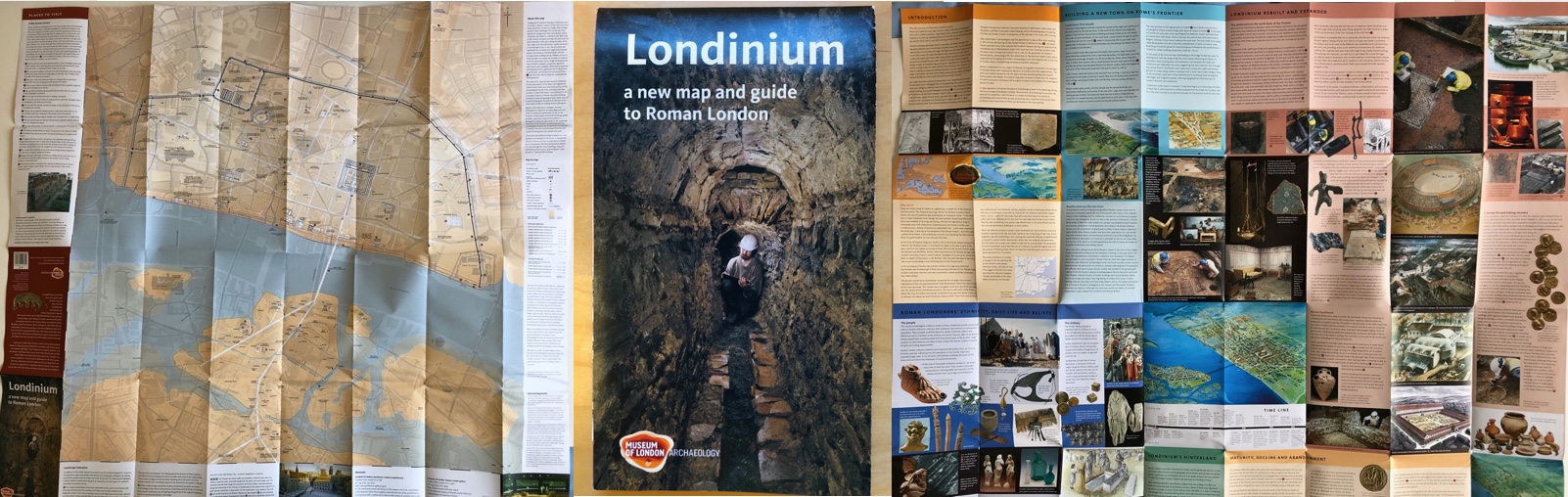

Although a little old fashioned in its displays, the Museum of London is a rewarding place to visit. The models are fascinating and so are the room reconstructions and the detailed history. I was disappointed in the shop which concentrated on London Underground merchandise, but then I found this terrific map:

Worth every penny and the best kind of souvenir!

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, INSURRECTIO and RETALIO. CARINA, a novella, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories, are now available. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. NEXUS, an Aurelia Mitela novella, will be out on 12 September 2019.

Download ‘Welcome to Roma Nova’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email newsletter. You’ll also be first to know about Roma Nova news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Fascinating. Thank you.

Delighted you enjoyed it, Pamela. It’s a place well worth visiting.

Haven’t been to the Museum of London, but I did get to see the Buried Hoard exhibit when it was at the British Museum.