Romans in the 21st century? Possibly provocative, but a perfectly feasible venture into alternative history fiction. How do you do this with no historical foundation?

Romans in the 21st century? Possibly provocative, but a perfectly feasible venture into alternative history fiction. How do you do this with no historical foundation?

Setting a story in the past or in another country is already a challenge. But if you invent the country and need to meld it with history that the reader already knows, then the task is doubled.

Unless writing post-apocalyptic, the geography and climate must resemble the ones in the region where the imagined country lies. And no alternate history writer can neglect their imagined country’s social, economic and political development. This sounds dry, but every living person is a product of their local conditions. Their experience of living in a place, and struggle to make sense of it, is expressed through culture and behaviour.

Norman Davies in Vanished Kingdoms: The History of Half-Forgotten Europe reminds us that:

…in order to survive, newborn states need to possess a set of viable internal organs, including a functioning executive, a defence force, a revenue system and a diplomatic force. If they possess none of these things, they lack the means to sustain an autonomous existence and they perish before they can breathe and flourish.

I would add history and willpower as essential factors.

So these are the givens. How do writers weave them into their stories? The key is plausibility. Take a character working in law enforcement. Readers can accept cops being gentle or tough, enthusiastic, intellectual or world-weary. Law enforcers come from all genders, classes, races and ages and stand in different places along the personal morality ruler. But whether corrupt or clean, they must act like a recognisable form of cop. They catch criminals, arrest and charge them and operate within a judicial system. Legal practicalities may differ significantly from those we know, but they must be consistent with that society while remaining plausible for the reader. But a flashing light and an oscillating siren on a police vehicle are universal symbols that instantly connect readers back to their own world.

So these are the givens. How do writers weave them into their stories? The key is plausibility. Take a character working in law enforcement. Readers can accept cops being gentle or tough, enthusiastic, intellectual or world-weary. Law enforcers come from all genders, classes, races and ages and stand in different places along the personal morality ruler. But whether corrupt or clean, they must act like a recognisable form of cop. They catch criminals, arrest and charge them and operate within a judicial system. Legal practicalities may differ significantly from those we know, but they must be consistent with that society while remaining plausible for the reader. But a flashing light and an oscillating siren on a police vehicle are universal symbols that instantly connect readers back to their own world.

Almost every story written hinges upon implausibility – a set-up or a problem the writer has purposefully created. Readers will engage with it and follow as long as the writer keeps their trust. One way to do this is to infuse, but not flood, the story with corroborative detail so that it verifies and reinforces the original setting the writer has introduced. Even though my book is set in the 21st century, the Roma Novan characters say things like ‘I wouldn’t be in your sandals (not ‘shoes’) when he finds out.’ And there are honey-coated biscuits (Honey was important for the ancient Romans.) not chocolate digestives (iconic British cookie) or bagels in the squad room.

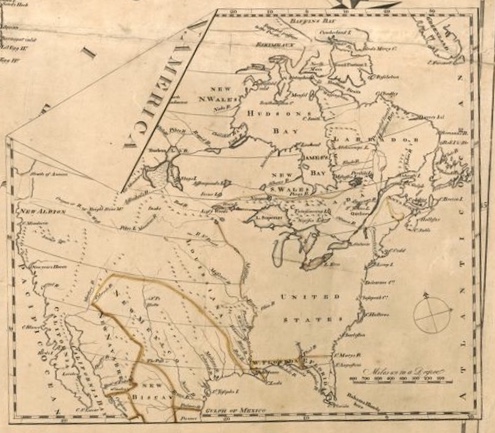

Inset in the map “The United States according to the definitive treaty of peace signed at Paris Sept. 3d. 1783. William McMurray, Robert Scot”

In my first novel, INCEPTIO, the core story of a twenty-five year old New Yorker who faces total disruption to her life when a sinister government enforcer compels her to flee to her dead mother’s mysterious homeland in Europe could be set anywhere. But I’ve made New York an Autonomous City in the Eastern United States (EUS) that the Dutch only left in 1813 and the British in 1865. The New World French states of Louisiane and Québec are ruled by Gouverneurs-Généraux on behalf of Napoléon VI; California and Texas belong to the Spanish Empire; and the Western Territories are a protected area for the Indigenous Peoples. These are background details as the New World is only the setting for the first few chapters. But as J K Rowling knew with Harry Potter’s world, although you don’t put it in the books, you have to have worked it all out in your head.

So, how to do this?

1. Decide on your Point of Divergence [POD] from real timeline history

Research this to death; know the political set-up, religion, customs, dress, food, agriculture, geography, economy, legal background, defence forces, cultural attitudes, everyday life of all classes and groups. These are the building blocks for your alternate society.

Illustrating this with Roma Nova:

In AD 395 [fixing the POD], three months after the final blow of Theodosius’ last decree banning all pagan religions [political/legal set-up], over four hundred Romans loyal to the old gods [religious background], and so in danger of execution, trekked north out of Italy to a semi-mountainous area similar to modern Slovenia [geography]. Led by Senator Apulius at the head of twelve senatorial families [social/political background], they established a colony based initially on land owned by Apulius’ Celtic father-in-law [cultural – intermarriage with non-Romans]. By purchase [land-management], alliance [politics] and conquest [normal Roman behaviour!], this grew into Roma Nova.

2. Know how you want your society to be and develop it with historic logic

If your story world doesn’t hang together, you will break a reader’s trust. You can have a fantastic world, such as Romans and steampunk but it needs to have reached that place in a plausible way. Writers need to provide motivation, whether personal or political or just forced by circumstances from outside. In my modern Roma Nova world, women are prominent.

This seems a long way from the ancient world where Roman attitudes to women were repressive [starting point]. But towards the later Imperial period [moving time on] women gained much more freedom to act, trade and own property and to run businesses of all types [social and economic development]. Divorce was easy, and step and adopted families were commonplace [standard Roman social custom].

Apulius, the leader of Roma Nova’s founders, had married Julia Bacausa, the tough daughter of a Celtic princeling in Noricum. She came from a society in which, although Romanised for several generations, women in her family made decisions, fought in battles and managed inheritance and property [non-Roman values introduced]. Their four daughters [next generation] were amongst the first pioneers [automatically new tough environment] so necessarily had to act more decisively [changing behaviour patterns] than they would have in a traditional urban Roman setting.

Given the unstable, dangerous times in Roma Nova’s first few hundred years [outside circumstances], eventually the daughters as well as sons had to put on armour and carry weapons to defend their homeland and their way of life [societal motivation]. So I don’t think that it’s too far a stretch for women to have developed leadership roles in all parts of Roma Novan life over the next sixteen centuries.

3. Keep some anchors to the readers’ pre-knowledge

Creating a story should be fun for the writer and the result rewarding for the reader. Although most writers like to encourage the reader to work a little and participate in the experience, writers shouldn’t bewilder readers. I mentioned plausibility earlier and how to inject corroborative details into the world being created. Anchors are equally important. For example, if you say “Roman legionary” most readers have an idea in their head already.

Taking Roma Nova as an example:

Roma Nova’s continued existence has been favoured by three factors: the discovery and exploitation of high-grade silver in their mountains [geography with a dollop of luck!], their efficient technology [historical fact], and their robust response to any threat [core Roman attitude]. Remembering their Byzantine cousins’ defeat in the Fall of Constantinople [known historical fact], Roma Novan troops assisted the western nations at the Battle of Vienna in 1683 to halt the Ottoman advance into Europe [known historical turning point]. Nearly two hundred years later, they used their diplomatic skills to help forge an alliance to push Napoleon IV back across the Rhine as he attempted to expand his grandfather’s empire [building on known historical person’s story].

4. Make the alternate present real

Writers need to imbue their characters with a sense of living in the present, in the now. This is their current existence, for them it’s not some story in a book(!). Character-based stories are popular; readers are intrigued by what happens to individual people living in different environments as well as taking part in major historical events. Sometimes it’s more interesting to follow the person’s story than the big event itself…

5. Go visible

Obviously, an imagined country is pretty hard to photograph. If you can draw, then you have the tools literally at your fingertips, but if like me your artistic skills are limited to turning out sketches of pin-men, then it’s back to the camera.

Images suggest tones, possibilities, and elements on which to base your ideas. Roma Nova is situated in the middle of Europe. I’m a European and have visited most countries, including a trip to Rome and Pompeii last year, so I have an idea of the countryside and cityscapes I’m looking for. The results are here; I refer back to them if I’m finding it difficult to visualise my characters in a particular location. Readers have loved them as well so it’s a double benefit.

Images suggest tones, possibilities, and elements on which to base your ideas. Roma Nova is situated in the middle of Europe. I’m a European and have visited most countries, including a trip to Rome and Pompeii last year, so I have an idea of the countryside and cityscapes I’m looking for. The results are here; I refer back to them if I’m finding it difficult to visualise my characters in a particular location. Readers have loved them as well so it’s a double benefit.

In summary, alternate history gives us a rich environment in which to develop our storytelling. As with any story in any genre, the writing must create a plausible world, backed by meticulous research, but the writer is, of course, the master of their universe.

Based on a post I wrote in 2013 for Daniel Ottalini’s blog Modern Papyrus

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, INSURRECTIO and RETALIO. CARINA, a novella, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories, are now available. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. NEXUS, an Aurelia Mitela novella, is now out.

Download ‘Welcome to Roma Nova’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email newsletter. You’ll also be first to know about Roma Nova news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Sound advice 🙂

Thanks, WriterChristophFischer. It’s very similar to the approach to any historical novel – loads of research intertwined with letting your imagination run riot, but with historical logic.

Ms. Morton, I just quoted a portion of your post (the section leading up to the sandal example) in a Kindle review of Robyn Carr’s Swept Away to illustrate why little details make for a great read. I hope you will find that I did justice to your post. Jon

That’s fine, Jon. Do let me have the URL for your review.

[…] 20th and 21st centuries and hence alternative history. You can read more about alternative history here but in the meantime, let's hear a little more about Alison […]