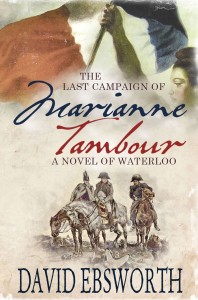

A welcome return visit from my writing friend David Ebsworth telling us about his next project …

1815. The 200th anniversary is looming. A passion for the Napoleonic period is tugging at my writing hand. Yes, I thought, my next one will be about Waterloo. But from what angle?

I began looking for the real-life experiences of women who may have been on the battlefield itself, rather than mere observers. And there were many. Like the story of Jenny Jones, from Talyllyn, and the other soldiers’ wives who accompanied the British army. But then I came across the tale of the beautiful Frenchwoman, in cavalry uniform, found among the dead by Volunteer Charles Smith, 95th Rifles, where the fighting had been thickest during that hot June afternoon.

It occurred to me that we don’t have too many English-language novels that look at the Hundred Days from a French perspective. And I also couldn’t remember reading anything about the French women who might have been present at Waterloo. So I began to read everything available on Frenchwomen and their relationship to the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Suddenly, as often happens when we research for historical fiction, I found myself in a very different world. One in which women were not confined to simply following the army, and perhaps helping to tend the wounded at the battle’s end, or nurse the fever cases, but in which there was a well-established tradition of women soldiers or, at least, of women who thought little of being in the centre of the action. Feisty women. A gap had opened up, a void that begged to be filled. So the research for The Last Campaign of Marianne Tambour began in earnest.

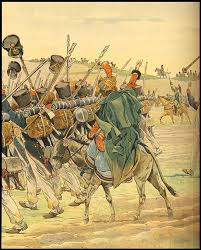

And I loved writing this story. It was finally inspired when I read a factual account of French Napoleonic cantinière, Madeleine Kintelberger, who served with Bonaparte’s 7th Hussars during the Austerlitz campaign and was caught up in fighting against the Russian Cossacks while protecting her children who were also with her on the battlefield. Her husband had been killed by cannon fire and Madeleine held off the Cossacks with a sword that she had picked up, losing her own right arm in the process. She was slashed by sabres and speared by lances during the same engagement, as well as shot in each leg. Yet she was also eight months pregnant with twins. It seems nothing short of a miracle that she survived at all. The Russians took her prisoner and she eventually returned to France with her children, where she was received in person by the Emperor and awarded a military pension. But the most astonishing aspect of all this was the fact that Madeleine was only one of hundreds of women serving in such positions in the French army’s front lines, many of them with similarly incredible tales to tell and yet largely ignored, both in fiction and non-fiction alike.

Then, almost immediately afterwards, I also came across the equally remarkable exploits of Marie-Thérèse Figueur who in 1793 had joined the French revolutionary army, though she had originally fought for the counter-revolutionary Federalists. But she enlisted as a cavalry trooper, all the same, in her own right as a woman, and served with distinction in various Dragoon regiments at Toulon, Savigliano-Genola, Ulm, Austerlitz, Jena, Burgos and the battles of the 1814 Campaign. She was captured, and escaped, both from the Austrians and, later, from Spanish guerrilleros, though not without suffering several serious wounds. Her reputation made her an object of curiosity in fashionable French society and she found herself invited to dinner with Bonaparte himself when he had still been First Consul of the Republic – the first of several face-to-face meetings with Napoleon. She was not present at Waterloo, however, since she had retired in 1814 and opened a table d’hôte restaurant in Paris – though that was certainly not the end of her adventures. Once again, her story was unusual but not unique.

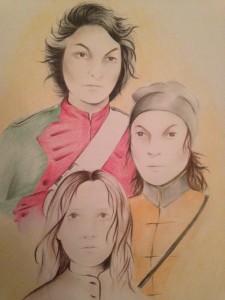

So the proposition was simple. What if two fictional women, but based on the real-life characters of Kintelberger and Figueur, were brought together by something more than a simple twist of fate during Bonaparte’s final campaign, in June 1815, that culminated in the Battle of Waterloo? And what if that “something” had a mystical element that would have been very typical of the age’s flirtations between the scientific and the spiritual? The result: two of the most feisty women ever to hit the pages of historical fiction – Dragoon trooper, Liberté Dumont, and the eponymous Imperial Guard cantinière, Marianne Tambour, each of them easily capable of putting Richard Sharpe to shame. I hope readers enjoy them as much as I enjoyed the telling of their tale!

You can follow the exploits of Dumont and Tambour in David Ebsworth’s novel, The Last Campaign of Marianne Tambour, due to be released on 5th December.

You can follow the exploits of Dumont and Tambour in David Ebsworth’s novel, The Last Campaign of Marianne Tambour, due to be released on 5th December.

David Ebsworth is the pen name of writer, Dave McCall, a former trade union negotiator, born in Liverpool (UK) and now living in North Wales. He has published three previous novels: The Jacobites’ Apprentice, Finalist in the Historical Novel Society’s 2014 Indie Award; The Assassin’s Mark, set during the Spanish Civil War; and The Kraals of Ulundi: A Novel of the Zulu War. Each of these books has been the recipient of the coveted B.R.A.G. Medallion for independent authors.

More details of David’s work are available on his website: http://www.davidebsworth.com

STOP PRESS: Out now!

Amazon Kobo

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers, INCEPTIO, and PERFIDITAS. Third in series, SUCCESSIO, is now out.

Find out about Roma Nova news, writing tips and info by signing up for my free monthly email newsletter.

Hey Alison, thanks for posting this. And I’m obviously happy to chat about the content if anybody’s got questions or comments.

Fascinated to read this, Dave, as I was preparing the post. A real piece of hidden women’s history!

It will be good I know, David is passionate about his history and enjoys the research as much as the writing that’s for sure.

Definitely ordering a copy!