Spring – awakening from winter sleep, the celebration of new life, blossoms and fertility. In many religions, the revival from the dead and a fresh start.

Until the arrival of Christianity, Easter did not exist as a festival for Romans. So how did they mark the arrival of spring? We have three alternatives: Cerealia, Parilia and Floralia.

Ovid hints at its archaic, brutal nature of the Cerealia (held for seven days from mid to late April) when he describes a nighttime ritual; blazing torches were tied to the tails of live foxes, who were released into the Circus Maximus.

The origin and purpose of this ritual are unknown; it may have been intended to cleanse the growing crops and protect them from disease and vermin, or to add warmth and vitality to their growth.

Ovid suggests that long ago, at ancient Carleoli, a farm-boy caught a fox stealing chickens and tried to burn it alive. The fox escaped, ablaze; in its flight it fired the fields and their crops, which were sacred to Ceres. Ever since, foxes are punished at her festival.

The ludi Ceriales – games were essential to any Roman festival – were held in the Circus Maximus. Ovid mentions that Ceres’ search for her lost daughter Proserpina was represented by women clothed in white, running about with lighted torches.

During the Republican era, the Cerealia was organised by the plebeian aediles (minor public magistrates), Ceres being one of the patron deities of the plebs or common people.

The festival included circus games (ludi circuses), opening with a horse race in the Circus Maximus, with a starting point just below the Aventine Temple of Ceres, Liber and Libera. After around 175 BC, the Cerealia included ludi scaenici, theatrical performances.

The annual festival of the Parilia on 21 April, intended to purify both sheep and shepherd, was in honour of Pales, a deity of uncertain gender who was a patron of shepherds and sheep.

Ovid describes the Parilia at length in the Fasti, an elegiac poem on the Roman religious calendar, and implies that it predates the founding of Rome, traditionally 753 BC, as indicated by its pastoral, pre-agricultural concerns.

During the Republic, farming was idealised and central to Roman identity, so the festival took on a more generally rural character. Increasing urbanisation caused the rustic Parilia to be reinterpreted rather than abandoned, reflecting Rome’s traditionalist nature.

During the Imperial period, the date was celebrated as Rome’s ‘birthday’ (dies natalis Romae).

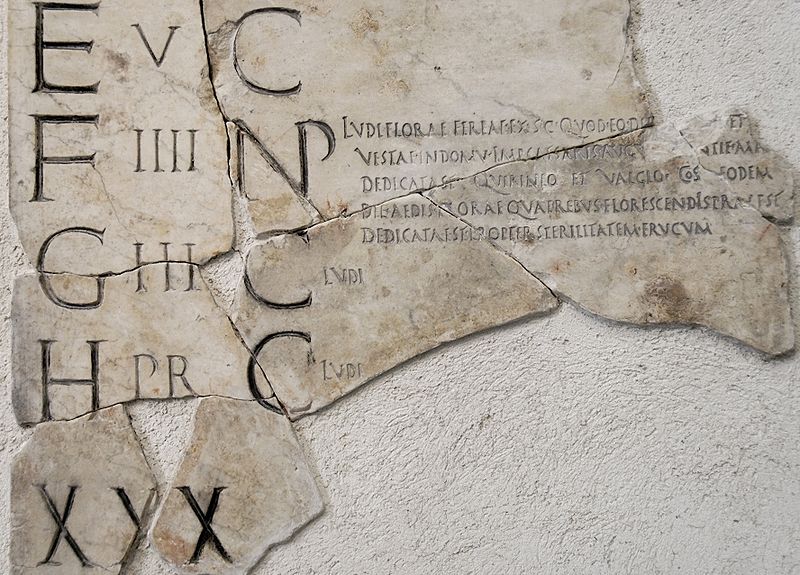

And lastly, the Floralia celebrated the goddess Flora, and took place on 27 April during the Republican era, or April 28 on the Julian calendar. It began in Rome in 240 or 238 B.C. when the temple to Flora was dedicated to invoke the goddess’s protection of blossoms, essential to the life cycle of food-producing plants.

The Floralia fell out of favour and was discontinued until 173 BC, when the senate, concerned about wind, hail, and other damage to the flowers, ordered Flora’s celebration reinstated as the ludi Florales (or ludi Florae). (See Ovid Fasti 5.292 ff and 327 ff.). Under the Empire, the games lasted for six days.

The festival had a licentious, pleasure-seeking atmosphere and in contrast to festivals based on Rome’s archaic patrician religion, the games of Flora had a plebeian character.

The games of Flora were presented by the plebeian aediles and paid for by fines, and probably partly by these aediles, who used the games as a socially acceptable way of gaining popularity and so votes in future elections for higher office.

Cicero mentions his role in organising the Floralia games when he was aedile in 69 BC. (Orationes Verrinae ii, 5, 36-7). The festival opened with theatrical performances (ludi scaenici), and concluded with competitive events and spectacles at the Circus and a sacrifice to Flora. In 30 AD, the entertainments at the Floralia presented under the future emperor Galba (then a praetor) featured a tightrope-walking elephant.

Participation of prostitutes

Prostitutes participated in the Floralia; according to the satirist Juvenal, prostitutes danced naked and fought in mock gladiator combat. Many prostitutes in ancient Rome were slaves, and even free women who worked as prostitutes lost their legal and social standing as citizens, but their inclusion at religious festivals indicates that sex workers were not completely outcast from society.

Symbols

Ovid says that hares (Aha!) and goats – animals considered fertile and salacious – were ceremonially released as part of the festivities. Persius says that the crowd was pelted with vetches, beans, and lupins, also symbols of fertility.

Ovid says that hares (Aha!) and goats – animals considered fertile and salacious – were ceremonially released as part of the festivities. Persius says that the crowd was pelted with vetches, beans, and lupins, also symbols of fertility.

In contrast to the Cerealia, when white garments were worn, multi-coloured clothing was customary. There may have been evening ceremonies, since sources mention measures taken to light the way after the theatrical performances.

1700 year old Berryfields egg

And eggs? In Rome, the egg symbolised life and fertility and was used in the rites of Venus (the patroness of the month of April). An egg preceded the religious procession for Ceres, goddess of agriculture (see Cerealia above).

Macrobius wrote that in the rites of Liber, Roman god of fertility and wine (who was also called Bacchus and identified with Dionysius), eggs were honoured, worshipped, and called the symbol of the universe, the beginning of all things.

Eggs are represented on Roman sarcophagi, perhaps with the wish that the spirit of the departed may have a renewal of life.

And today?

In Romania, Palm Sunday is called Duminica Floriilor, a name derived from Floralia; as often happened, the name of a long established Roman festival was given to a Christian feast celebrated during the same season.

But in Roma Nova, along with other traditional Roman festivals, Carina and family celebrate Floralia. However, it doesn’t always turn out to be the happiest of times especially when the blue-uniformed custodes are hammering on the door as in SUCCESSIO…

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email newsletter. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Wow, I did not know that Easter did not exist as a festival for Romans until the Christians arrived. Now I must ceremonially release a bunny and wear multi-coloured clothing or should I wear white?

Well, the colour of you clothing depends on whether you’re feeling pure and restrained or a little bit naughty! I love the idea of having a variety of festivals so you can choose one to suit your personality. But I suspect they joined in every one – the Romans were both traditionalist and superstitious. And who doesn’t like a holiday? 😉

I do like hares. I saw one in real life, once. Very special, majickal creatures!

Thank you for another interesting post, Alison. Happy hopping!

Helen x

Hares are powerful creatures, slightly sinister, too, and I believe they pack a good punch! Really pleased to have shown two Roman ideas – eggs and hares – have been picked up for the Christian Easter.

[…] Morton : Roma Nova – How the Romans Celebrated […]

[…] Alison Morton : Roma Nova – How the Romans Celebrated Spring http://www.alison-morton.com/2014/04/17/how-the-romans-celebrated-spring-2/ […]

Interesting post, although I got utterly stuck on the comment re Allegra. Will you PLEASE hurry up and get that book out there???? Have tweeted

The next book, SUCCESSIO, is out in June. There’ll be a cover reveal and other info in the next newsletter this weekend…

I’ve seen a hare too, they are amazing animals… I suppose we owe Easter to the Romans in more senses than one – perhaps if there had been no crucifixion we’d still be celebrating versions of Cerealia etc, though I would hope without the animal cruelty thrown in. Fascinating blog!

Yes, I’m not too keen on the fox burning. Lindsey Davis puts it in her recent novel and the heroine’s not too enthusiastic either, but LD writes for her 21st century audience. 😉

In Roma Nova, the main festivals are celebrated as in ancient times, but with some differences, and no foxes.

[…] Morton : http://www.alison-morton.com/2014/04/17/how-the-romans-celebrated-spring-2/ How the Romans Celebrated […]

A great post. I remember spotting a hare when I was a girl and thought how sinister they look. Thank you for sharing. Looking out for your next book! Have a great easter x

Thank you, Caz. I believe they’re quite tough, not at all like ‘Easter bunnies’ we think are so cuddly. But then, the Romans were fairly tough themselves…

[…] Helen Hollick : Let us Talk of Many Things – Fictional Reality. 2. Alison Morton : Roma Nova – How the Romans Celebrated Spring 3. Anna Belfrage : Step inside… – Is freezing […]

Leaving a quick comment as I’m battling flu 🙁 this post looks so interesting, I’m calling back when I feel a bit better to devour it!

I love the Roma Nova series – its fascinating how you’ve blended to old Empire with present day!

So sorry to hear about the ‘flu – rotten luck!

I’ll send a prayer to Asclepius for you.

Ahhhh spring and sex and rebirth. It seems everyone enjoyed enjoyed leaving the dead of winter and cold/cooler temps for such delights. Love this article. Thank you

Thanks, JF, Yes, spring pleases our heads, our hearts and the visceral attachment to life that’s been inside us for thousands of years.

What diverse ways of celebrating spring! The first one with the foxes’ tails set on fire is atrocious. And using the spring games to gain political support for future elections, sounds like that one is still in use.

Thanks,Denise. Yes, the fox thing shows how austere the priests were and how casual to life yet superstitious of it the Romans were in general.

[…] http://www.alison-morton.com/2014/04/17/how-the-romans-celebrated-spring-2/ […]

Thank you, Alison. I certainly learned a lot from your post, not least that the Romans seemed to know well how to enjoy themselves. It always surprises me that, here in France, Good Friday is not a public holiday.

Glad you enjoyed the post, Peter.

Good Friday is like any other day – the blessing of living in a secular state! But I notice SuperU is closed on Monday…

The Romans certainly grasped life to the full, didn’t they?! I think I would rather not have been a fox, though…A truly comprehensive study of the Roman festivities around this period, thank you Alison!

Thanks, Isabel. Yes, they were a strong, robust lot, and had none of the guilt we seem to be beset by. But they were very observant in their own way and the gods filled their lives in a way we probably find difficult to understand. A good party and a few days’ games were never a bad day, though…

[…] http://www.alison-morton.com/2014/04/17/how-the-romans-celebrated-spring-2/ […]

A fascinating post. Just down the round from our home here in Milngavie is the site of the Antonine Wall, built in AD 142 though abandoned within a couple of decades when the Romans retreated back to Hadrian’s Wall. Although we have lived here for over 20 years, I remain touched by the idea that we reside in a place that was the very northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire. In my book, I state that – put simply and in a modern context – “the Romans got as far as HomeBase”.

A lovely thought, John!

Talking of Roman frontiers, there may have been a very early one in Scotland garrisoned in the AD 70s. Have a look at this: http://www.theromangaskproject.org.uk/index.html

Gosh, those Romans never did things by halves, did they, Alison?! Makes our own celebrations with Easter bunnies and eggs seem very tame, for those of us who are not religious, anyway – though my 10-year-old daughter was happy to cast aside her professed atheism last Sunday to join the procession from the village pond to the church, waving palms and following a very pretty little brown donkey!

Something for everybody in each festival, but religion was deeply ingrained in the superstitious Romans, a rather primordial side we forget about when we think of their technology and artistic achievements.

Thanks to everybody who left a comment. The giveaway is now closed. Back soon with the winner’s name…

Okay, I put the names in the hat – it was so difficult otherwise.

And the winner is…

Ginger Dawn Harman.

Congrats to her!

So informative. I love this. And Hilaria? Could that be linked to the origins of April Fools’ Day?

Not quite so sure abut that, Maria.

Hilaria alludes to general rejoicing , but is associated with Cybele who is not altogether the most cheerful of religious figures given her association with castration. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hilaria for a quick introduction)

Romans loved jokes, especially boisterous, practical ones, so I suspect there was more general foolery all year round.