When looking at Julia’s home town of Virunum in an earlier post, I sketched lightly over Roman involvement. Never a good idea… Seriously, it was a long relationship lasting from the 2nd century BC through to the 5th century AD.

Dealing with Rome

The Celts of Noricum had discovered around 500 BC that their local deposits of iron ore made superior steel, so they built up a major metalworking industry. Traces have been found on the Magdalensberg (the pre-Virunum settlement on the hill) of a major production and trading centre where specialised blacksmiths crafted metal products, including sophisticated tools and weapons.

By 200 BC, the tribes of Noricum had united into one kingdom, the Regnum Noricum. During the Republican period, the Romans discovered the high quality of the weapons coming out of Noricum and, never ones to miss an opportunity, started negotiations with the Regnum Noricum and its craftsmen.

The resulting trade agreements led to the kingdom becoming a key ally of Rome, benefitting from Roman military protection in exchange for the constant supply of high-quality products.

The proverbial hardness of Noric steel is even expressed by Ovid: “…durior […] ferro quod noricus excoquit ignis…” which roughly translates to “…harder than iron which Noric fire tempers [was Anaxarete towards the advances of Iphis]…”.

Erzberg today (Photo: CC licence, Gerald Senarclens de Grancy)

The iron ore was quarried at two mountains in modern Austria still called Erzberg (‘ore mountain’ in German) today, one at Hüttenberg, Carinthia and the other at Eisenerz (‘iron ore’ in German!), Styria, with only 70 km between them. The latter is the site of the modern Erzberg mine.

Back to Roman times… Noricum thus became a major provider of weaponry for the Roman armies from the mid-Republic onwards and a strategic asset that needed protection.

This was demonstrated in 113 BC, when the German tribes Teutones and Cimbri invaded Noricum. In response, the Roman consul Gnaeus Papirius Carbo led an army over the Alps to repel these Germanic tribes. He ambushed them near Noreia (wherever that was). Although Carbo had the advantage in terrain and surprise, his forces were overwhelmed by the sheer number of tribal warriors and roundly defeated. He was afterwards accused by Marcus Antonius (yes, that one) for losing the battle through incompetence. Convicted, Carbo committed suicide rather than go into exile.

Noricum (West). Circa 170-150 BC. Silver tetradrachm (21mm, 12.09 g, 12h). Kugelreiter type (Photo: Carlomorino CC Licence)

Roman rule

For a long time, the Noricans enjoyed independence under their own local rulers while continuing to trade profitably with the Romans. In 48 BC, they took the side of Julius Caesar in the civil war against Pompey – a savvy move.

However… (you knew there was going to be a ‘however’…)

In 16 BC, having joined with their neighbouring Pannonians in invading Histria, they were defeated by Publius Silius Nerva, proconsul of Illyricum – not such a good move.

For all its virtues, Rome was a robust military society which did not tolerate rebellion or invasion. As a result, Noricum was annexed and, although called a Roman province, it was not organised as such but remained a kingdom with the title of Regnum Noricum, yet under the supervision of an imperial procurator.

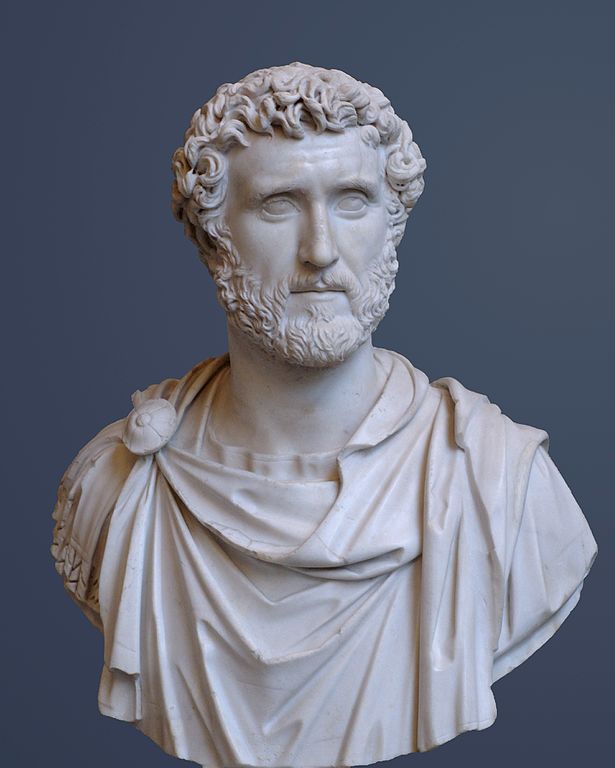

For practical reasons, mostly trade and administrative creep, Noricum was fully integrated into the Roman Empire during the reign of Claudius and apparently the Noricans offered little resistance. It was only in the time of Antoninus Pius (AD 138–161) that troops in the form of the Second Legion Pia (later renamed Italica) were stationed in Noricum; their commander became the governor of the province.

Under Diocletian (AD 245–313), Noricum was divided into Noricum ripense (Noricum along the right bank of the Danube, the northernmost part of the original province), and Noricum mediterraneum (landlocked Noricum, the southern, more mountainous area). Each division was administered by a civilian governor called a praeses, and both belonged to the diocese of Illyricum in the Praetorian prefecture of Italy. But pragmatism often led to a praeses leaving fully Romanised local community leaders like Julia’s father to manage local affairs.

Noricum and Christianity

Rome’s many nationalities practised widely different forms of religion, but all priests and communities recognised the overarching authority of the emperor, especially as he was the pontifex maximus (chief priest) for the whole empire. Diocletian and his immediate successors strongly promoted the traditional Roman pantheon of gods.

When members of the Christian cult refused to make sacrifice to the established gods, which included deified past emperors, they were deemed by the emperor to have rejected imperial rule, i.e. committed treason. And treason tended to have only one outcome.

In AD 304, Florianus, a Christian serving as a high-ranking imperial military commander in Noricum who had amongst other achievements set up an extremely effective firefighting unit, refused to sacrifice and was executed. He was later canonised as Saint Florian and to this day is the patron of firefighters in the German-speaking world.

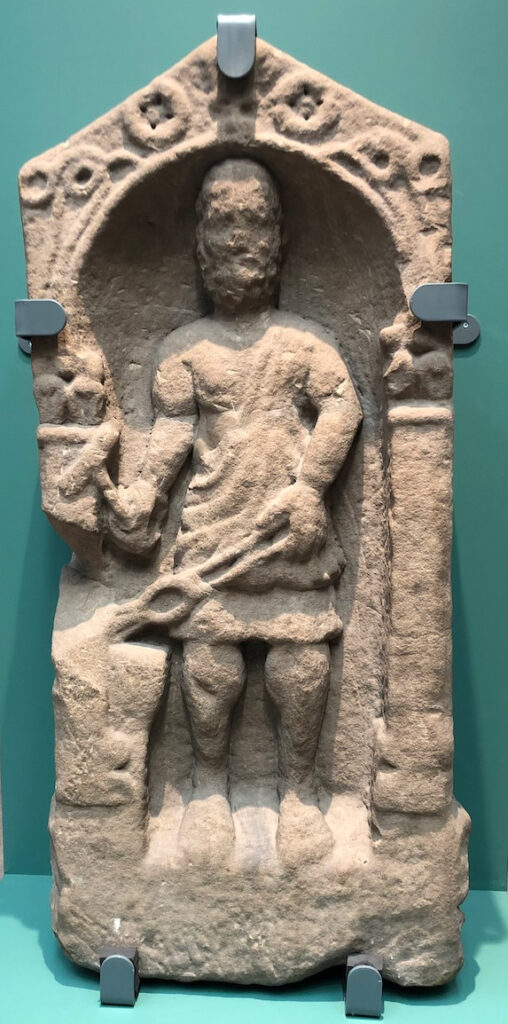

Traditional religion still flourished in Noricum and a new temple to the god Mithras, especially revered by the military, was dedicated in Virunum around AD 311.

Mithras relief, originally from Rome, now in the Louvre (Photo: CC Licence by Jastrow)

Only when Constantine (reigned AD 306–337) became emperor, and in practice only from AD 312, did Christianity begin to take hold in Noricum. By AD 343, there were at least five bishops with well-established circuits of congregations. By the end of the fourth century, statues of gods in the Virunum baths quarter had been destroyed.

In the fifth century, enthusiastic Christian mobs smashed the most important shrines and traditional temples throughout Noricum. Pagan cults survived in patches as late as the second half of the fifth century, but those practising the rites were officially shunned and courting death.

Proof of an early Christian church, whose existence had been presumed for a long time, has recently been found in the northern section of Virunum.

The transition from Roman to barbarian rule in Noricum is well documented in Eugippius‘ Life of Saint Severinus, providing information which could be used as possible examples in other regions where primary sources from the period are lacking.

———

Knowledge of Roman Noricum has been extensively documented by Géza Alföldy in his work Noricum (Routledge, 1974, rev. 2014) to which I am much indebted.

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. JULIA PRIMA, Roma Nova story set in the late 4th century, starts the Foundation stories. The sequel, EXSILIUM, is out on 27 February 2024.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Thank you for this information. I have studied Mithraism a bit and find it fascinating.

It’s very much a soldiers’ cult and fascination in its rituals. I’m so glad you enjoyed it.