Unless you write for the sole purpose of personal fulfilment, you probably hope other people will read your work. When you publish a story, either as a freebie or commercially on multiple channels (Amazon, Kobo, Waterstones, iBooks) and in multiple formats (paperback, hardback, ebook, audio), you are making a contract with the reader. The reader invests their time and money and in return you agree to provide a satisfying reading experience. Of course, defining ‘satisfying’ is the legendary poisoned chalice, but let’s hope it’s a genre or type of thing they would normally enjoy reading. It all boils down to taste.

Unless you write for the sole purpose of personal fulfilment, you probably hope other people will read your work. When you publish a story, either as a freebie or commercially on multiple channels (Amazon, Kobo, Waterstones, iBooks) and in multiple formats (paperback, hardback, ebook, audio), you are making a contract with the reader. The reader invests their time and money and in return you agree to provide a satisfying reading experience. Of course, defining ‘satisfying’ is the legendary poisoned chalice, but let’s hope it’s a genre or type of thing they would normally enjoy reading. It all boils down to taste.

The reader has picked your book, attracted by the cover, and read the product description (or blurb on the back). Expectation x 1. If it’s a new novel by an author they’ve read before, they (like me) pick it up immediately with only a glance at the description because they know it’s going to be good. Expectations x 10. They fish out their hard earned money and buy it. Yippee!

Promises, promises

From the very first page, the writer makes a promise to the reader, one that they must deliver on by the end of the book. Let’s look at genre. Romance readers will throw your book against the wall and tell all her friends on Facebook what a rubbish writer you are if there is no ‘happy ever after’, or at least ‘happy for now’ ending. A crime reader will get angry if the intrepid sleuth declares that he just can’t see whodunnit and asks what’s for tea. And fantasy readers will be be after you with the Axe of Ullshorn and a crowd of elves if there’s no magic.

From the very first page, the writer makes a promise to the reader, one that they must deliver on by the end of the book. Let’s look at genre. Romance readers will throw your book against the wall and tell all her friends on Facebook what a rubbish writer you are if there is no ‘happy ever after’, or at least ‘happy for now’ ending. A crime reader will get angry if the intrepid sleuth declares that he just can’t see whodunnit and asks what’s for tea. And fantasy readers will be be after you with the Axe of Ullshorn and a crowd of elves if there’s no magic.

Protagonists leap in

Usually a story starts with the protagonist, hopefully in some kind of difficulty, or with a difficulty that’s about to fall onto the protagonist. Sometimes, it starts with something inconsequential, but that takes over the protagonist’s whole existence. We expect to go through the whole story with that person, see the person grow and change, and survive the story. If the protagonist does not survive, then the reader should know that from the start. It’s an unfair deception otherwise.

Seeing clearly

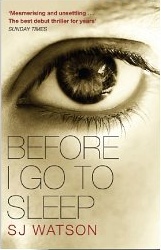

The reader expects you to keep the story clear whether it’s a deep, stylish unpicking of a character on a personal inner journey, a lighthearted shopping and friends story or an action adventure ‘twists and turns’ thriller. Of course, a mystery has to be devious. e.g. think of S J Watson’s Before I Go To Sleep, a wondrously deceptive book, but very clearly written. You can combine types of story, e.g. historical whodunits, but these range from Lindsey Davis’ straightforward tales about the cynical, witty and dumped-upon Falco to Umberto Eco’s labyrinthine and literary, but eminently readable The Name of the Rose.

The reader expects you to keep the story clear whether it’s a deep, stylish unpicking of a character on a personal inner journey, a lighthearted shopping and friends story or an action adventure ‘twists and turns’ thriller. Of course, a mystery has to be devious. e.g. think of S J Watson’s Before I Go To Sleep, a wondrously deceptive book, but very clearly written. You can combine types of story, e.g. historical whodunits, but these range from Lindsey Davis’ straightforward tales about the cynical, witty and dumped-upon Falco to Umberto Eco’s labyrinthine and literary, but eminently readable The Name of the Rose.

Avoiding bumpiness and dreariness

Apart from clear, evocative writing, readers expect a book to be well-structured with a beginning, middle and end – that’s obvious – but they also don’t want a bumpy ride along the way. Spending a a paragraph or two describing the glint of a knife as it slides into the sheath strapped on the protagonist’s smooth-skinned shapely leg sets up an expectation that the knife or maybe the shapely leg will play an important part in a future scene. Nor do we need to see a sunset graphically described for a page.Thanks to Google and friends’ photos on social media most people know what a spectacular sunset looks like. However, if that sunset is relevant to a crucial scene, then a description is fine, but only for a sentence or two!

Minor character misuse

You introduce a minor character into your novel because you’ve promised your BFF, your mother, or somebody who won inclusion as a prize in a charity draw. You give them a different name, talk about their penchant for quail’s eggs or fatty chips, give them a shining waterfall of chestnut locks, or spots and a grotesque tattoo, and you write some snappy dialogue in their speech register. They fetch a file, order in food, visit a cousin, then disappear. If that’s all they do, there is no point to their existence and you have wasted words as well as bewildered, and probably annoyed, the reader. Secondary characters have one purpose only – to help drive the story forward. They are not interesting otherwise.

You introduce a minor character into your novel because you’ve promised your BFF, your mother, or somebody who won inclusion as a prize in a charity draw. You give them a different name, talk about their penchant for quail’s eggs or fatty chips, give them a shining waterfall of chestnut locks, or spots and a grotesque tattoo, and you write some snappy dialogue in their speech register. They fetch a file, order in food, visit a cousin, then disappear. If that’s all they do, there is no point to their existence and you have wasted words as well as bewildered, and probably annoyed, the reader. Secondary characters have one purpose only – to help drive the story forward. They are not interesting otherwise.

Endings

And lastly, no alien space bats/dei ex machina,/waking up from dreams/new characters to the rescue to conclude the story. My favourite hate is when the author kills off the character for no good reason. Sacrifice, a terminal illness (leave clues, please) and suicide because they’ve been found out are all perfectly acceptable, though. 😉 Of course, a twist is fabulous and in my books, mandatory, but there have to be clues laid throughout the book. In a totally unofficial poll in respect of INCEPTIO, one or two people guessed the twist, quite a number knew by halfway something was brewing but didn’t know what and the paranoid among my friends said, ‘I know what you’re like – there’s bound to be something.’

Make the book have a purpose for the reader – a problem to solve, a character to change, a lesson to learn, or what’s the point?

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers, INCEPTIO, and PERFIDITAS. Third in series, SUCCESSIO, is out early summer 2014.

Can’t argue with anything you say, Alison.

Thank you, Gilli! I think sometimes in our efforts we forget why the reader buys our books. What they want is a good read and it’s our job to deliver. Simples!

Good sensible advice. Hope I’ve taken it in the writing of my own trilogy!

Having read two out of the three manuscripts, Denise, I’d say you have.

I agree about the promise to the reader I know a guy who wrote a murder mystery where you didn’t find out who did it. Though I enjoyed the novel until the end, I did feel let down by the ending – stretching the boundaries of genre is one thing, but not finding out who did it is another.

Oh, Graeme, that is unacceptable. I’d be tempted to name and shame. The writer should at least leave you with a strong hint even if he murderer isn’t disclosed in an obvious way.